Lamashtu is one of the most dreaded demonic entities in ancient Mesopotamian mythology—a female demoness who preyed on pregnant women and newborns, embodying the raw fears of childbirth and early infancy in a world where maternal and infant mortality loomed large.

Arising from the polytheistic traditions of Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria, she operated independently of the major gods, acting on her own malevolent whims rather than divine command. This unique autonomy marked her as both a goddess and a monster in her own right.

Often depicted in incantation texts and protective amulets, Lamashtu was blamed for miscarriages, sudden infant deaths, fevers, and nightmares—ills that ancient healers attributed to her insatiable hunger for human blood and flesh.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Primary: Lamashtu (Akkadian); Sumerian: Dimme or Dim3-me; also Kamadme. She bore seven names, often called the “seven witches” in incantations. |

| Title | Plague Demon; She Who Erases; Daughter of Anu; Fallen-down-from-Heaven. |

| Origin | Mesopotamian (Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian). |

| Gender | Female. |

| Genealogy | Daughter of sky god Anu (Sumerian An); no mother specified; occasional links to earth goddess Ki in later interpretations. |

| Role | Infant-killing demoness; bringer of disease, miscarriage, and chaos to childbirth. |

| Associated Deity/Figure | Pazuzu (rival wind demon, invoked as protector); Inanna (occasional identification in incantations); Marduk (occasional confronter in protective rites). |

| Brings | Miscarriage; infant death; fevers; nightmares; blood-drinking; bone-gnawing; crop blight; river infestation. |

| Weaknesses | Repelled by Pazuzu amulets; incantations invoking heaven/earth; rituals with figurines, sacrifices (piglet hearts, bread, water); burial of effigies near walls. |

| Realm/Domain | Arbitrarily roams human world, especially homes during labor; exiled from heaven. |

| Weapon/Item | Dagger (depicted in some amulets); long talons and blood-stained hands as natural weapons. |

| Symbolism | Envy of fertility; chaos in creation; maternal peril; untamed wilderness versus civilized order. |

| Sources | Cuneiform incantation series (SpTU I, YOS 11, RA texts); Neo-Assyrian amulets; medical tablets like those in Farber’s edition; Old Babylonian rituals. |

Who or What is Lamashtu?

Lamashtu is a horrifying entity—a demoness whose very name evoked shivers among ancient mothers and healers. Neither fully goddess nor mere spirit, she straddled the divine and infernal, wielding power unchecked by the pantheon’s hierarchy.

Born of the sky god Anu—yet cast out for her wickedness—Lamashtu symbolized the perils of procreation: she slipped into birthing chambers like a thief in the night, her claws poised to snatch unborn babes or strangle the newly born.

Texts describe her not as a servant of greater evils, but as an autonomous force—cruel, raging, predatory—who thirsted for the vitality denied to her barren form. This independence terrified the Sumerians and Akkadians alike. Unlike tempests sent by Enlil or plagues from Nergal, Lamashtu’s assaults required no cosmic warrant, making her a personal, unpredictable foe.

“Lamashtu” Meaning

The name Lamashtu carries a chilling etymology embedded in the Akkadian tongue spoken by the empires of Babylon and Assyria.

Derived from the verb lašāmu, meaning “to erode” or “to efface,” it translates starkly as “she who erases”—a name that captures her essence as the unmaker of life, the silent thief who wipes away the promise of newborns from their mothers’ arms.

This linguistic accuracy reflects Mesopotamian precision in naming threats; just as dimme (her Sumerian precursor) evoked feverish plagues, Lamashtu connoted dissolution—the gradual fading of vitality, like ink bleeding from wet clay.

Researchers trace the term’s evolution from early Sumerian Dim3-me, possibly linked to dimma (“fever demon”), suggesting an ancient fusion of medical and mythic fears—where unexplained infant woes were not mere ailment, but erasure by a divine hand.

Beyond literal meaning, Lamashtu’s terminology was entangled in the fabric of incantatory magic, where her seven epithets—“the seven witches“—amplified her multiplicity, implying she struck from seven directions or guises (much as the Pleiades stars portended doom).

This polyonymy (common in Akkadian demonology) served dual purposes: enumeration contained chaos (by binding her facets in verse), while invoking terror through repetition.

In broader Semitic roots, echoes appear in later Aramaic lamashtu-like terms for “devourer,” hinting at cross-cultural ripples—perhaps influencing Hebrew lilit (night hag) or Arabic qarina (child-strangler).

How to Pronounce “Lamashtu” in English

In English, pronounce Lamashtu as lah-MAH-sh-too—stressing the second syllable with a soft “ah” like in “father,” followed by a hushed “sh” and a drawn-out “oo” as in “boot.”

The initial “la” flows lightly, avoiding a hard “luh,” to mimic the fluid Semitic phonetics; think of it as “lah” with a gentle aspirate, not unlike “lama” in “llama” but truncated.

Practice by breaking it: lah (skyward lift), MAH (deep resonance), sh-too (fading snarl).

Origins

Lamashtu’s genesis unfolds amid the fertile floodplains of Mesopotamia, where Sumerian city-states like Uruk and Eridu birthed the world’s earliest writing around 3100 BCE—cuneiform scratches on clay that first whispered her name as Dimme, a fever-bringer tied to the dim haze of illness.

By the Akkadian Empire’s rise (c. 2334–2154 BCE), she crystallized into Lamashtu, daughter of Anu, the remote sky father whose vastness mirrored her untethered malice.

Unlike primordial chaos like Tiamat, confined to cosmic epics such as the Enuma Elish, Lamashtu haunted the domestic sphere—slipping through reed-thatched doors to afflict the hearth.

Her origins blend medical treatise and myth: Old Babylonian tablets (c. 2000–1600 BCE) prescribe exorcisms against her, revealing how Sumerian plague spirits evolved into Akkadian personal demons, reflecting societal shifts from communal ziggurat worship to intimate household rites.

Genealogy

Lamashtu’s lineage anchors her in the celestial heights, yet highlights her isolation: as sole progeny of Anu, the unapproachable sky god, she inherits vast power without the bonds that tether other deities.

Ancient tables mention no mother for this powerful demoness. However, Ki (Earth) appears in sp,e Babylonian variants, likely implying a union of opposites that birthed discord.

| Relationship | Details |

|---|---|

| Parents | Father: Anu (sky god); occasional mother: Ki (earth goddess) in later Babylonian lore. |

| Siblings | None specified. |

| Spouse | None; barren and unloving. |

| Children | None; her envy drives assaults on human offspring. |

You may also enjoy:

What Is Jorōgumo? The Deadly Spider Woman of Japanese Myth

February 2, 2026

Who Was Ravana in Hindu Mythology and Why Was He Feared?

October 3, 2025

Palis: The Foot-Licking Desert Jinn That Drinks Your Blood

December 3, 2025

Barbas: The Lion Demon Who Spreads Disease

March 3, 2026

Demon Alastor: The Grand Executioner of Hell

November 17, 2025

Arati: The Beautiful Demon of Aversion in Buddhist Mythology

October 15, 2025

Sources

Lamashtu permeates Mesopotamian texts not through standalone epics but through incantation series—practical grimoires in which her depredations frame protective spells.

Chief among these is the canonical Lamaštu Series (SpTU I, compiled c. 1st millennium BCE), a trilogy of tablets blending Sumerian hymns and Akkadian rituals, edited in modern compilations like Walter Farber’s Lamaštu: An Edition.

Earlier Old Babylonian fragments (YOS 11) offer some proto-incantations. At the same time, Neo-Assyrian medical papyri (RA texts) mention her as a source for several deadly diseases.

| Source | Quote |

|---|---|

| SpTU I (Canonical Lamaštu Series, Tablet I) | Great is the daughter of Heaven who tortures babies / Her hand is a net, her embrace is death / She is cruel, raging, angry, predatory / A runner, a thief is the daughter of Heaven / She touches the bellies of women in labour / She pulls out the pregnant woman’s baby / The daughter of Heaven is one of the Gods, her brothers / With no child of her own. / Her head is a lion’s head / Her body is a donkey’s body / She roars like a lion / She constantly howls like a demon-dog. |

| YOS 11, 20 (Old Babylonian Incantation) | Lamaštu, daughter of Anu, / who roams the streets like a wild ass, / who drinks the blood of the innocent, / who gnaws the bones of the newborn— / begone to the steppe, to the mountain wastes! |

| RA Incantation (Thureau-Dangin Text) | Lamash, daughter of Anu / Whose name has been uttered by the gods / Innin, queen of queens / Lamashtu, O great lady / Who seizes the painful Asakku / Overwhelming the Alû / Come not nigh what belongeth to the man / Be conjured by Heaven / Be conjured by the Earth / Be conjured by Enlil / Be conjured by Ea. |

| CT 14 (Medical Tablet Fragment) | The demoness Dimme, fallen from heaven, / touches the child with dirty hands; / she spreads defilement, causes fever— / recite thrice: Ea and Asalluhi bind her! |

| BM 120022 (Neo-Assyrian Amulet Inscription) | Lamashtu of the seven seas, / bearer of the dagger, / who rides the ass through doors unbarred— / Pazuzu drives you back, son of Hanbi scatters your winds! |

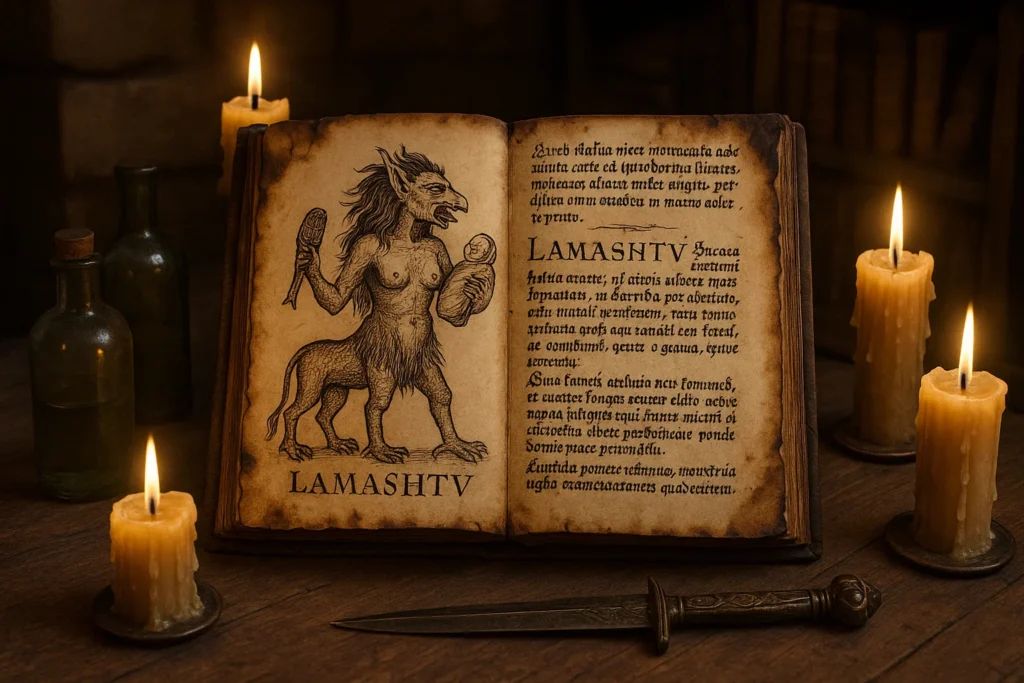

What Does Lamashtu Look Like?

Lamashtu is described in a frightening, unsettling way, embodying both the beauty of a human and the wildness of an animal, creating an image that evokes disgust. She is a shocking figure, representing the darker side of fertility.

Her head resembles a lion’s but features floppy donkey ears, which seem silly against her wild, tangled hair. Her mouth is wide, filled with jagged teeth that look ready to tear into flesh.

Her eyes are fierce and hungry, like a predator’s, with slits like a cat’s, rimmed with bloodshot redness. Rather than nurturing, her breasts drip not milk but a toxic fluid that damages everything it touches.

Her body is hairy and rough, reminiscent of a wild animal, yet it has a human shape. Her arms are long and thin, ending in claw-like fingers stained with blood.

Lower down, her body transforms further: she has strong donkey legs that allow her to move quietly and bird-like feet that leave sinister marks on the ground.

Snakes slither from her hands, acting like living whips or feeding from her breasts alongside piglets and other small creatures—this makes for a disturbing picture of motherhood, where she seems to nurture these beasts grotesquely.

Artifacts from ancient Nimrud—dating back to 934–610 BCE—depict her this way: sitting on a donkey, she holds daggers that look like tools for childbirth but are, in fact, threatening, ready to strike.

Enemies, Rivals, and Allies

Lamashtu is often described as a solitary demon, whose anger sets her apart from others like her. This isolation brings her into conflict with powerful beings who protect humans.

One of her biggest rivals is Pazuzu, a wind demon known for being fierce yet paradoxically offering protection to the weak. Legends tell of him stepping on images of Lamashtu on amulets, using his scorpion tail to scare her away with his mighty roar.

Their rivalry may arise from shared ancestry or a cosmic competition, leading people to believe in the idea of using one terrifying force to fight another. For instance, mothers carried symbols of Pazuzu to keep Lamashtu’s evil at bay.

Kind gods like Ea (also known as Enki) and Enlil appear in spells meant to bind Lamashtu, keeping her confined to remote areas. Marduk, a hero who defeated chaos, occasionally appears in Babylonian rituals as her major foe, just as he defeated the great dragon Tiamat.

Despite her formidable nature, Lamashtu lacks allies. Her independent spirit fosters distrust even among other demons, such as Alû (who brings nightmares) and Asag (who spreads disease). Rather than teaming up, she has been known to overpower them using spells.

Lamashtu is sometimes associated with her “seven witches,” ghostly aspects that act like extensions of her power. While they can strengthen her attacks, they disappear when it comes time to drive her away.

In broader tales, she also interacts with Lilitu, another figure known for seduction and haunting children. Over time, Lamashtu seems to have absorbed some of Lilitu’s traits, and their rivalry plays out in ancient stories, often resolved by the power of exorcists.

Connections to Other Entities

| Name | Genealogy | Type | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pazuzu | Son of Hanbi (wind god) | Protective wind demon | Lion/dog head, wings, scorpion tail, talons |

| Lilitu | Offspring of Anu | Seductive storm spirit | Winged woman, owl feet, long hair |

| Alû | Underworld lurker | Nightmare causer | Faceless humanoid, shadowy form |

| Asag | Chaos spawn | Disease monster | Rock-like giant with multiple heads |

| Ugallu | Hybrid guardian | Doorway sentinel | Lion head, human body, eagle feet |

| Udug | Evil spirit clan | Personal afflicter | Horned, clawed humanoid |

| Namtar | Messenger of Ereshkigal | Plague bringer | Skeletal figure with venomous gaze |

| Rabisu | Ambush demon | Stalker of the unwary | Reptilian, lurking in shadows |

| Anzû | Primordial bird | Tablet thief | Lion-headed eagle |

| Mušmaḫḫū | Serpent hybrid | Venomous chaos agent | Seven-headed snake with lion paws |

| Uridimmu | Mad dog demon | Rabies inflicter | Dog-headed man with scorpion tail |

| Gello | Greek import | Child-killer hag | Haggard woman with bat wings |

| Lilith | Adam’s first wife (later lore) | Night demoness | Winged seductress with serpentine lower body |

| Qarīna | Arabic jinn variant | Cradle rocker | Shapeshifting woman, often invisible |

| Tiamat | Primordial mother | Saltwater chaos | Dragon-serpent with multiple heads |

Lamashtu Myths, Legends, and Stories

The Descent of the Fallen Daughter

In the grand, star-filled realm of Anu, where even gods must follow rules, lived Lamashtu—a bright but troubled spirit. She was surrounded by her powerful siblings but felt a deep longing for the life of mortals on Earth.

Her father, An, noticed her growing frustration as she watched mortals carry children while she remained empty inside.

“Why do humans get what I can’t?” she shouted into the emptiness, her voice echoing through the heavens.

Annoyed, An confronted her: “Daughter, your feelings are too wild for this place. Go down to Earth, or I will cast you out!”

Defiant, she took a piece of forbidden clay—the stuff of existence—and escaped. But An didn’t let her go without punishment. He hurled bolts of blue fire, sending her crashing down to the dry wastelands below.

When she hit the ground, Lamashtu transformed from a beautiful spirit into a terrifying creature: her once graceful face twisted into a monstrous form, with fierce jaws and sharp claws.

Freed from the rules of Heaven, she wandered freely, starting with the flocks of sheep, stealing the lives of lambs to satisfy her hunger. Then she grew bolder and entered a village where a bride dreamed of having children.

Under the soft glow of the moon, Lamashtu crept into the bridal chamber, cold breath chilling the sleeping woman’s skin. “Give me your promise of a child,” she whispered, her claws grazing the woman’s belly.

The terrified bride woke up screaming for help, but by morning, the room was stained with blood, and hope had vanished.

News of the creature that haunted families spread quickly, robbing them of their future happiness with a mere touch. Healers began to tell her story in birthing rooms, warning: “As Anu has cast her out, may she be banished forever!”

The Sevenfold Assault on the Cradle

In a small village near the bend of the Euphrates River, where the date palms seemed to whisper secrets, there lived a woman named Enhedu. She was pregnant and, during the harvest moon, felt the intense pains of labor. As she struggled, a creature named Lamashtu, known for causing trouble, appeared in various disguises.

First, she came as an old woman with a bone comb, pretending to offer help. “Rest, weary one,” the crone said, as she wove Enhedu’s hair, trying to soothe her.

Trusting the woman’s kind face, Enhedu fell asleep. But the old woman quickly revealed her true self, transforming into a sinister figure.

“This child isn’t meant for you,” Lamashtu hissed. With a fierce grip, she took the unborn baby away, devouring its spirit and leaving behind only echoes of cries.

When dawn broke, Enhedu awoke to find her child pale and weak, already suffering from a fever. But Lamashtu wasn’t finished. She returned in different forms: as a barking dog that scattered protective charms, a shadowy figure that poisoned Enhedu’s milk, and in several other frightening guises.

A witch was stirring up illness, a snake was wrapping around Enhedu’s ankle to cause pain, and a roaring monster that haunted her when she tried to sleep. The final form was that of a pig that filled the baby’s breath with wheezing sounds.

As the situation worsened, the village elders gathered for help, calling upon a priest to intervene. He took clay and shaped it into a strange figure that resembled Lamashtu, with donkey ears, and recited powerful words to banish her. They also made offerings, including bread, water, and the heart of a pig, and buried them at the wall of the village.

On the third day, as dusk fell, they buried the clay figure. Suddenly, winds picked up, carrying away Lamashtu’s frustrated cries. With the demon driven off, Enhedu’s baby became strong and healthy by the morning.

You may also enjoy:

Apophis: The Great Serpent of Egyptian Chaos

November 11, 2025

Amaymon: The Infernal King Who Commands Death and Decay

November 17, 2025

Hariti: The Demon Mother Who Fed on Children at Night

December 8, 2025

What Is Baku? The Japanese Yōkai That Eats Nightmares

January 28, 2026

Who Was Ravana in Hindu Mythology and Why Was He Feared?

October 3, 2025

Who Was Hiranyakashipu, the Demon King of Hindu Mythology?

October 6, 2025

The Rivalry of Winds

In the ancient city of Assur, where thunderstorms carried important messages, there lived Pazuzu—a powerful spirit known for bringing harsh winds that dried up crops and toppled buildings.

One day, he heard distressing news about his long-time enemy, Lamashtu. She had invaded a royal nursery, harming a young prince and causing chaos within the palace. Upset by her actions, Pazuzu roared, “Enough of this!” His mighty wings spread wide like storm clouds, and he vowed to confront her.

Following her to her lair by the river, where the water was filthy and plants were dying, Pazuzu found Lamashtu waiting with a dagger in her hand and a mocking smile.

“Wind-brother,” she taunted, “your winds only mock my desires. Join me, or watch everything wither away!” Fueled by anger, Pazuzu charged at her, pushing her against the muddy ground.

Their fight was fierce, shaking the Earth and uprooting trees. “I bring a drought that you fear,” he yelled, “yet I protect the weak from your destruction!”

In the chaos, Lamashtu managed to grab one of his wings, drawing blood. Still, Pazuzu retaliated by unleashing a blast of dry air that shriveled her serpents.

Wounded and furious, she retreated to the underworld, threatening, “You protect them now, but I will unleash seven storms soon!”

With scars from their battle, yet determined to stand strong, Pazuzu had artists create a bronze image of the fight, depicting him as the victor over Lamashtu.

The Bribe of the Reed Boat

In the shadowy canals of ancient Babylon, where the temples of Ishtar sparkled with gold, a potter’s wife was heavily pregnant with twins. She was working hard, but her labor was disturbed by an ominous sign: a stray jackal howling at the gate.

This creature was linked to Lamashtu, a fearsome demon, who crept closer at midnight, her shape shadowy and mysterious. She called out softly, offering the woman a bronze pin to help ease her pain. However, when the woman reached out, she noticed the demon’s hairy limb, and she screamed to Shamash, the sun god.

Quickly, the elders of the community rushed to help. They brought a small reed boat, carrying a clay figure of Lamashtu. The boat was adorned with offerings like jewelry and a comb made of lapis lazuli.

The priest urged them to use these gifts to send the demon away, chanting a spell to appease her: “You who destroys hope, take this small tribute and leave us in peace!” They set the boat afloat on the canal, filled with sweet treats and a heart from a puppy.

Drawn by the offerings, Lamashtu took the bait, mistakenly believing the clay figure was a real prize. As the boat drifted towards the marshes, it seemed that some external force, perhaps from Pazuzu, carried her far away.

The potter’s wife felt relief as her twins were born safely, and the fever that had troubled her vanished.

Lamashtu Powers and Abilities

Lamashtu was a powerful figure with a unique kind of strength. Instead of causing massive disasters (as storm gods such as Adad did), her abilities were more subtle and insidious. She thrived on breaking down life in quiet, painful ways.

As the daughter of the sky god Anu, she had a special kind of freedom that allowed her to move through the mortal world without any restrictions. This independence made her more dangerous since no one could call on the higher gods to protect them from her.

Lamashtu’s real strength lay in her ability to create fear and suffering. She would invade people’s dreams, filling them with terrifying nightmares that made them feel helpless.

She could also blight plants, leaving families without food. Her actions could start as personal curses but quickly spread, causing problems for entire communities.

While she was not as powerful as ancient deities like Tiamat, who could unleash vast oceans, Lamashtu focused on inflicting deep pain on individuals.

A single touch from her could devastate entire families, and her terrifying grip was as effective as the deadly plagues sent by Namtar. Still, she aimed specifically at mothers and their children.

Lamashtu’s powers and abilities include:

- Infant Theft: Slips unseen into chambers to extract unborn or suckle newborns’ blood, gnawing bones for essence; leaves victims pale, fevered, or vanished.

- Fever Induction (Antasuḫḫa): Spreads “dirty hands” defilement, igniting burning plagues that mimic chaff-fire; targets mothers post-labor, eroding strength over days.

- Nightmare Binding: Whispers illusions that paralyze sleepers, causing muscle lock or hallucinatory assaults; often precedes physical strikes.

- Crop and Water Blight: Infests rivers with unseen filth, wilts fields to famine—secondary harms amplifying maternal despair.

- Shapeshifter: Manifests as seven witches (crone, beast, shadow); each facet enables infiltration, from helpful midwife to stray hound.

- Venomous Touch: Talons inject a wasting curse, causing miscarriage or cot-death; blood-stained nails symbolize perpetual sustenance from victims.

- Howl of Madness: Roars summon envy-driven wrath, inciting temporary insanity in witnesses—lion-bellow that echoes as demon-dog wail.

Rituals, Amulets, and Protective Practices

In ancient Mesopotamia, people took special steps to protect themselves from the fearsome Lamashtu. They performed various rituals that combined magical practices and medical knowledge, often within the home. These rituals involved chants from priests and offerings from everyday people, all aimed at persuading, controlling, or driving away Lamashtu.

One of the key texts describing these practices was “Evil Eradicated.” The rituals focused on keeping Lamashtu at bay: they used figurines to represent her, made sacrifices to satisfy her, and called upon powerful cosmic forces for help.

Women who were pregnant, midwives, and healers called āšipu carried out these rituals regularly, seeing childbirth as a crucial battle against this demon.

Incantations and Ceremonies

In ancient Mesopotamia, there were special rituals to protect mothers and newborns from the demoness Lamashtu, believed to cause illness and misfortune. Priests led these intricate ceremonies to drive away her harmful influences.

A key part of the ritual involved creating a small figurine representing Lamashtu. This figurine, made of clay or bronze and adorned with her signature features—donkey ears and snakes —had a piglet’s heart placed in its mouth to symbolize the life force she supposedly stole from others.

The priests would offer bread and water to the figurine, treating it as a meal to appease Lamashtu. They also recited special incantations three times a day, calling upon the god Ea to weaken her powers.

On the third evening of the ritual, the figurine was buried near a wall, which represented the boundary between the known world and the wild. Black dogs were included in the ceremony as guardians to bark and help chase Lamashtu away from the community.

The texts of the incantations, preserved in cuneiform script, showcase the deep poetic traditions of the time, blending Sumerian hymns with Akkadian prayers.

One from the RA series (Thureau-Dangin edition) adjures her thus:

Lamash, daughter of Anu

Whose name has been uttered by the gods

Innin, queen of queens

Lamashtu, O great lady

Who seizes the painful Asakku

Overwhelming the Alû

Come not nigh what belongeth to the man

Be conjured by Heaven

Be conjured by the Earth

Be conjured by Enlil

Be conjured by Ea.

Another, from SpTU I (Tablet II), details her form to bind it:

Great is the daughter of Heaven who tortures babies

Her hand is a net, her embrace is death

She is cruel, raging, angry, predatory

A runner, a thief, is the daughter of Heaven

She touches the bellies of women in labor

She pulls out the pregnant woman’s baby

The daughter of Heaven is one of the Gods, her brothers

With no child of her own.

Her head is a lion’s head

Her body is a donkey’s body

She roars like a lion

She constantly howls like a demon-dog.

Amulets and Talismans

Amulets designed to protect against Lamashtu, a demon associated with illness and danger to mothers and children, were made from materials such as lapis lazuli, bronze, and bone. These small objects were worn by mothers or hung over cradles to keep the demon away.

One of the most famous types of these amulets featured Pazuzu, a wind demon, shown triumphantly overcoming Lamashtu, as depicted in images from the 9th to 7th centuries BCE. The plaques depicted Pazuzu with his fierce head above Lamashtu’s body and a scorpion tail ready to strike.

Inscribed on these talismans were spells such as “Pazuzu, son of Hanbi, scatters Lamashtu’s winds,” which were believed to counteract Lamashtu’s harmful influence.

Expectant mothers often held onto these amulets during labor, feeling that Pazuzu’s powers could protect them and their babies. Simpler items like safety pins or combs were placed in tiny model boats with images of Lamashtu to distract her from seeking out humans, as a sort of offering.

Additionally, yellow alabaster amulets found at Nimrud bore full spells on one side and images of seven animal-headed protectors on the other, creating a barrier against Lamashtu.

These artifacts were discovered in large numbers and showed that people from different social classes used them. At the same time, the wealthy might order gold versions, but common folks used clay ones.

However, all featured a clever twist: they had her seven names written backward, which was believed to weaken her spells.

You may also enjoy:

Who Is Abalam in Demonology? The Terrifying King That Serves Paimon

September 30, 2025

Vritra: The Dragon Who Swallowed the Sky in Hindu Mythology

October 7, 2025

Who Was Ravana in Hindu Mythology and Why Was He Feared?

October 3, 2025

Tarakasura: The Dark Demon Who Ruled Hell on Earth

December 4, 2025

Who Is Taṇhā, the Seductive Demon of Craving in Buddhist Mythology?

October 15, 2025

Arati: The Beautiful Demon of Aversion in Buddhist Mythology

October 15, 2025

Frequenty Asked Questions

Was Lamashtu worshipped in Sumeria, or was she a demoness in Sumerian mythology?

Lamashtu, known as Dimme in ancient Sumerian texts, was not worshipped in temples or through rituals. Instead, she was feared as a dangerous demon believed to cause infant deaths and miscarriages. People in ancient Mesopotamia tried to protect themselves from her through exorcisms and the use of Pazuzu amulets, rather than showing her any reverence. She was seen as a chaotic outcast, representing the darker side of fertility.

How bad is Lamashtu?

Lamashtu is considered one of the most terrifying figures in Golarion’s mythology. She once killed the god Curchanus to gain control over animals. Still, she twisted this power to create monsters that threaten society. She transforms intelligent creatures into beasts and turns beauty into horror. In modern interpretations, she attracts outcasts into her cults, exploiting their pain and despair to promote chaos and destruction.

What were Lamashtu’s seven names?

Lamashtu bore seven secret names invoked in Akkadian incantations as “seven witches,” each a facet for binding her multiplicity—though exact epithets vary by tablet, like “Sword-that-splits-the-skull” or “She-who-kindles-fire.” These polyonyms contained her chaos, recited to enumerate and expel. Lesser-known: reversing them in spells unraveled her power, a linguistic weapon in ancient obstetrics.

Why is Lamashtu worship banned?

Lamashtu’s cults are forbidden in places like Absalom because they are known for creating monsters through horrific rituals, often endangering mothers and their children. Followers of Lamashtu would harm themselves, indoctrinate younger generations, and produce terrifying beings. Some even masquerade as helpful to infertile women, producing twisted offspring and presenting this as empowerment, blurring the lines between help and horror.

What is Lamashtu, the goddess of?

Lamashtu is known as the goddess of infant death, miscarriage, and monstrous births in Mesopotamian mythology. She embodies the jealousy that can twist fertility into something frightening. Her influence extends over fevers, nightmares, and the corruption of life at its beginnings, often associated with the idea of deformed children. In the fictional world of Pathfinder, she is expanded as the Mother of Monsters, championing a variety of strange and chaotic creatures.

Who defeated Lamashtu?

No one has ever truly defeated Lamashtu; she can only be pushed away or contained through rituals. Ancient stories mention that Pazuzu, a powerful being, used amulets and wind to repel her. Other rituals called upon gods like Ea and Enlil to bind her to desolate areas. Also, burying clay figures representing her was believed to send her away. Her continuous return highlights how people in ancient Mesopotamia viewed chaos as something that cannot be permanently eradicated.

What is the symbol of Lamashtu?

Lamashtu has several symbols associated with her. One of the main symbols is a dagger, representing blood and danger. She is often shown riding a donkey, which symbolizes a once-harmless creature now turned into a predator. Other symbols include piglets or snakes suckling from her, portraying her dangerous nature. These images, carved on bronze plates, were used to identify her and to ward off her threat.