Agubanba is a blind, cannibalistic female yōkai that preys on young women who have recently reached adulthood, luring them into peril with deceptive calls or sudden ambushes.

Unlike more widespread yōkai (such as the tengu or kappa), Agubanba remains deeply tied to local traditions. It’s not a well-known monster, but her presence warns against wandering alone in misty forests or near abandoned hearths.

According to various depictions, this malevolent spirit appears as an ancient crone, her sightless eyes clouded over like cataracts, her form twisted yet deceptively frail, often cloaked in tattered robes stained with the remnants of past feasts.

While benevolent yōkai might offer guidance, Agubanba represents unrelenting hunger.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Agubanba (primary); variants include Akubanba or ash-born hag in local dialects |

| Translation | Ash monk or gray priestess, evoking her emergence from hearth ashes |

| Title | Blind crone of the north; devourer of maidens |

| Type | Obake (shapeshifting spirit) or yamauba variant (mountain witch) |

| Origin | Born from neglected hearth spirits or cursed elders who died in isolation, gaining sentience through accumulated ash and resentment |

| Gender | Female |

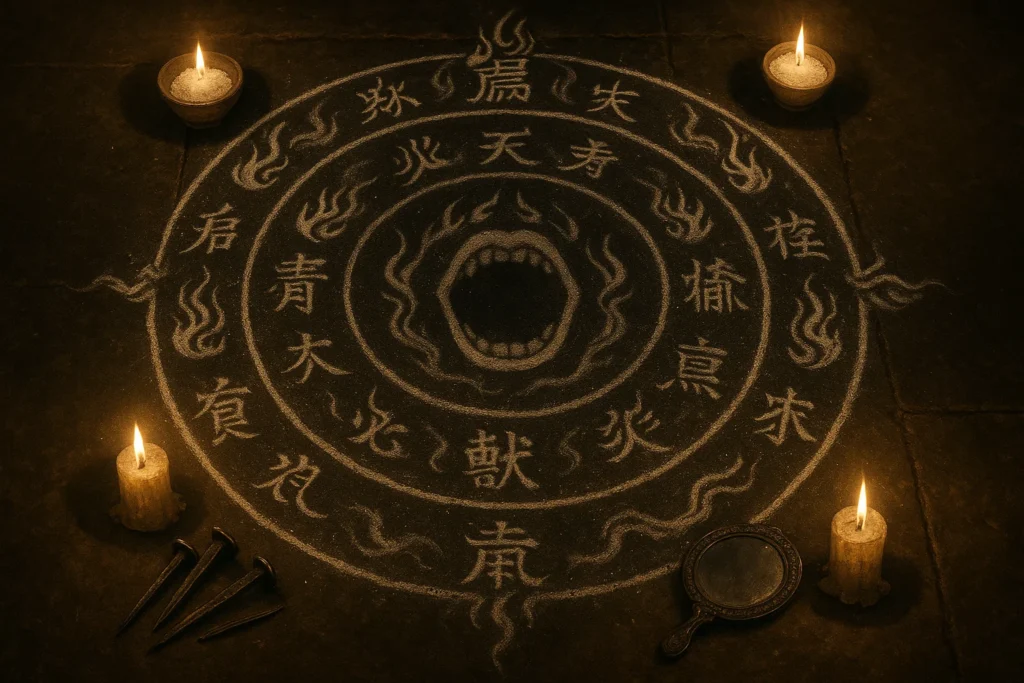

| Appearance | Elderly woman with milky, cataract-clouded eyes; wild, tangled hair matted with soot; emaciated frame hidden under ragged kimono; unnaturally large mouth on the crown of her head for devouring prey |

| Powers/Abilities | Blind navigation via acute hearing and scent; ash manipulation to obscure vision or summon illusions; rapid, claw-like strikes to immobilize victims |

| Weaknesses | Vulnerable to fire or salt scattered in hearths; repelled by rhythmic chants or iron tools struck together; sunlight weakens her form, forcing retreat to shadows |

| Habitat | Rural homes’ hearths in Akita and Aomori; foggy mountain paths and abandoned villages during twilight |

| Diet/Prey | Flesh of young women at the cusp of adulthood; occasionally stirs from ash to consume careless children playing near fires |

| Symbolic Item | Hearth ash, used to summon or banish her presence |

| Symbolism | Dangers of neglect in communal spaces; perils of adolescence and isolation in rural life; the transformative horror of aging without community |

| Sources | Local Akita folklore collections; Edo-period regional tales; modern compilations like Toriyama Sekien-inspired yokai encyclopedias |

Who or What is Agubanba?

Agubanba is a true terror in Japanese yōkai stories, a spectral hag whose blindness belies a predatory cunning honed by centuries of whispered warnings.

Interestingly, most stories and legends around this monster are rooted in the folklore of Akita Prefecture. Here, she personifies the dread of unseen dangers lurking in everyday spaces—particularly the hearth, where ash gathers like unspoken secrets.

As a female spirit (often classified as an obake or mountain witch), Agubanba typically targets those on the threshold of womanhood: girls who, having shed childhood, venture into the world with newfound independence.

On top of that, her assaults are not random. She typically strikes when young women are most vulnerable—such as fetching water at dusk or tending fires alone—transforming mundane chores into life-or-death gambits.

In broader yōkai lore, Agubanba aligns with other similar demonic entities (such as the yamauba—elderly crones exiled to the wilderness edges), but distinguishes herself through her affinity with ash and her terrifying maw (features that evoke both domestic intimacy and grotesque inversion).

“Agubanba” Meaning

The name Agubanba is linked to the northern Japanese dialects, its etymology revealing layers of domestic horror and spiritual ambiguity.

Derived from kanji as 灰坊主 (hai bōzu), it literally translates to “ash monk” or “gray priestess”—a paradoxical fusion where hai (灰) denotes the soot-laden remnants of hearth fires, and bōzu (坊主) traditionally refers to a Buddhist, often bald and ascetic.

This terminology suggests a desecrated sanctity: the yōkai as a fallen holy figure, emerging from profane ashes rather than sacred incense. In Akita’s patois, pronunciations soften to a-gu-ban-ba, longated vowels mimicking the hush of wind through chimneys, evoking her stealthy summons.

Historical records trace Agubanba’s name to the Edo period (1603–1868) regional gazetteers, where scribes adapted terms from Ainu-influenced Tohoku lore.

Early variants (like akubanba in Aomori tales) shift a-gu to imply “red ash” (aka hai), hinting at bloodied embers from her feasts—though scholars debate this as phonetic drift rather than intent.

By the Meiji era (1868–1912), as folklore compilations like those by Kunio Yanagita gained traction, the name standardized to Agubyōkai, emphasizing her monk-like tonsure—a smooth scalp save for the devouring mouth atop it—that inverts clerical purity into a carnal void.

In Iwate, she becomes amanjaku-uba, blending with “heavenly evil woman” motifs, in which ama (Heaven) corrupts into ash-born malice.

How to Pronounce “Agubanba” in English

Agubanba is pronounced in four parts: Ah-goo-bahn-bah. The emphasis is on the second part, “goo,” which has a soft “g” sound, similar to the one in “goose.” The “ahn” sounds similar to “on” in “song,” and the last part, “bah,” gently fades away.

What Does Agubanba Look Like?

Agubanba is a disturbing creature that turns the familiar image of an elderly woman upside down.

Her most striking feature is her eyes, which are completely white and cloudy. Even though she can’t see, there’s a sense that she’s acutely aware of her surroundings, as if her other senses have sharpened, making her a more formidable predator.

Her skin is pale and dry, clinging tightly to her bones, which jut out at strange angles. Although she appears weak and skinny, a hidden strength enables her to drag her victims into darkness with her long, claw-like fingers, which end in black talons.

Perhaps the most horrifying aspect of her appearance is the mouth on top of her head. It’s a large, gaping hole filled with sharp teeth that crunch loudly when she feeds. This bizarre mouth replaces the nostrils and lips, and it snaps shut quickly—like a trap—on unsuspecting prey.

She wears a tattered kimono that drips with dark stains, possibly blood or ash. While she doesn’t stand tall—similar to a hunched old woman—her shape can distort, stretching or compressing to fit through tight spaces.

Old illustrations from the Edo period sometimes depict her with whisker-like tendrils on her cheeks, resembling a cat. However, some purists argue that these were merely artistic details.

There are many different accounts of her appearance: some say her clothing seems to have melted to her skin, while others suggest that her cloudy eyes glow faintly, tricking people into feeling a connection to her.

Habitat

According to Japanese folklore, Agubanba inhabits the quiet and often misty rural areas of Tohoku (particularly in the Akita region). She is closely tied to the traditional hearth (irori)—a sunken fire pit found in many old Japanese homes.

Agubanba comes alive when the fire is low and twilight descends, creating a mysterious atmosphere. The warmth of the hearth is inviting, but it can also become a trap—her presence hidden in the soft glow of the flames, waiting for the right moment to appear.

Agubanba also roams the edges of mountains and forgotten paths in the foothills of Aomori. She’s drawn to the dense cedar forests where the mist wraps around everything like a soft blanket.

Folklore sometimes links her to the desolation that comes after harvest time—when autumn leaves decay and winter storms seal the valleys, forcing people indoors.

You may also enjoy:

Setcheh: Egypt’s Soul-Stealing Ancient Demon

November 11, 2025

Akateko: The Bloody Hand Ghost That Guards a Cursed Temple Tree

November 14, 2025

Who Is Andromalius and Why Is He the Last Demon of the Goetia?

January 20, 2026

What Is a Dīv? The Terrifying Giant Demon of Persian Myth

January 22, 2026

Who Is Ambolin, the Demon of Nighttime Dread

December 1, 2025

Who Is the Demon Andras, The Great Marquis of Discord?

January 15, 2026

Origins and History

Agubanba is an old demonic entity. She likely first appeared during the Heian period (794–1185), amid feudal fragmentation.

In northern Akita, where Ainu influences mingled with Yamato migrations, early agrarian societies faced relentless winters and isolation. So, tales of ash-born hags appeared as metaphors for the famine’s toll—women, burdened with hearth duties, vanishing into blizzards, their spirits warped by unfulfilled hunger.

Historical turmoils also amplified the legends. For example, the 11th-century Ōshū raids scattered clans, producing legends of cursed survivors haunting kin-fires. By the Kamakura era (1185–1333), as Zen asceticism spread, her “monkish” moniker parodied fallen clerics—blind to enlightenment, devouring the pure—reflecting Buddhism’s grip on rural psyches.

The Edo period in Japan (1603–1868) was a time of great wealth, but it also hid serious problems in rural areas. Rules set by local leaders restricted farmers’ freedom, leading to a sense of isolation. During this time, yōkai—such as Agubanba—became symbols of these restrictions, serving as guardians of community boundaries.

A great example is the Morioka records. In these texts, Agubanba served as a warning against the dangers of playing with fire, particularly for children who might accidentally summon spirits.

Natural disasters further shaped the tales of Agubanba. For instance, the eruption of Mount Unzen in 1792 coated northern Japan with ash, inspiring stories of a creature of volcanic fury with a fiery mouth spewing ash.

After World War II, as rural areas emptied out due to economic changes, Agubanba made a comeback in popular media. In the 1950s, she appeared in radio dramas that reimagined her as a ghost of the nuclear age, symbolizing the scars left by radiation.

Famous Agubanba Legends and Stories

The Ashen Lure of Odate Village

Once upon a time, in the quiet town of Odate in Akita Prefecture, there lived a girl named Saki. She was about to turn sixteen, a time when childhood starts to give way to adulthood.

Saki’s family were rice farmers who worked hard on their fields, and every evening they gathered around a small hearth in their home, where flames flickered like dancing spirits.

Saki, with her shiny black hair and rosy cheeks from her hard work, often found herself absentmindedly playing with the ashes in the hearth. At the same time, the older folks warned her to leave them be, saying, “Don’t stir the ashes, or you might wake something you don’t want to see.”

One evening, as the wind howled through the trees, her mother asked her to go get some spring water under the starlit sky. The path led her past old shrines, where moss-covered gates stood watch over forgotten gods.

With a lantern in hand, Saki sang a soothing lullaby that her grandmother used to sing, letting the soft melody chase away the evening chill. Suddenly, she heard a strange noise—not the rustling of leaves, but a scratching sound that made her stop.

Out of the shadows, an old woman appeared, hunched by a twisted oak tree. Her clothes were worn and ragged, and her eyes seemed clouded over. “Young one,” she croaked, her voice rough yet warm. “I’ve lost my way; can you help me find my home?”

Out of kindness, Saki thought of her own grandmother, who had spent years alone. “Of course, come with me,” she said, offering her arm.

The old woman gripped her tightly, her hands cold as if from the grave, but Saki pressed on, helping her along the way. As they approached the village, darkness loomed strangely around them, and Saki’s lantern began to flicker and dim.

“Why is the light going out so fast?” she asked, fear creeping in. The old woman laughed, a deep, unsettling sound. “Because the true night is just beginning, dear flower.”

In an instant, the woman transformed; her hair twisted wildly, and her face revealed sharp, yellowed teeth. Saki gasped in terror as the creature lunged toward her, its mouth wide open, ready to attack.

Thinking quickly, Saki hurled the lantern at the old woman, and its glass shattered, sending flames bursting forth. The creature shrieked in pain as the fire spread, burning her tattered robes and lighting the darkness.

Saki ran back towards her home, gasping for breath, only to find that the hearth was overflowing with ashes, swirling mysteriously.

In a panic, she remembered a protective tradition from her grandmother: she grabbed some salt from the kitchen and scattered it across the doorway, chanting, “Return to the ashes, spirit of hunger; purity will keep you out!” The trembling stopped, and smoke rose gently into the morning sky, as if everything had sighed in relief.

When dawn arrived, villagers discovered blackened ground where the creature had been, with no sign of the old woman except for some scratch marks on a nearby tree.

Though Saki eventually married and started a new life, she never forgot that night. She made sure to always respect the ashes in the hearth, passing down her story as a warning: sometimes showing kindness to the wrong spirit can lead to danger.

The Maiden’s Echo in Aomori’s Whispering Pines

In the quiet valleys of Aomori, where whispering pines share secrets with the darkened sky, lived Hana—a young woman whose twentieth birthday meant she would soon be married.

Her village, situated at the foot of the Hakkoda Mountains, adhered to traditional customs. Their homes were surrounded by stone lanterns that flickered like watchful eyes against the night.

Hana, graceful and full of laughter, often wandered along the forest’s edges to collect moss for dye, singing to lift her spirits. The elders warned her, “Be careful, girl; Agubanba is lurking. She has a craving for brides, especially as weddings draw near.”

One autumn evening, as leaves turned deep red under the harvest moon, Hana ventured further into the woods—moss was hard to find after the early frost. The twilight sky cast a purple haze; her path twisted into a dense thicket where branches crossed like whispering friends.

Suddenly, she heard a cry—not the usual sounds of the forest, but a sorrowful voice: “Help me, sweet girl; shadows are swallowing this lost soul!” Hana stopped and saw a frail old woman hunched against a moss-covered tree, her head down and her hands reaching out as if she were blind.

Her cloudy eyes sparkled like frozen stones, and her hair was matted and messy. Feeling a surge of compassion, Hana said, “Don’t be afraid, grandmother; I’ll help you find your way.”

The old woman stood up, leaning heavily on Hana. Despite her frail appearance, there was something oddly strong about her, pulling Hana further into the darkness.

The crone began to tell tales of her youth, lost to wars, of children scattered far away, and of long, cold nights spent searching for warmth. Hana felt a pang of sorrow for the woman’s struggles, which mirrored her own fears about leaving her family for a stranger’s home.

“Stay with us tonight,” Hana offered. “My father’s fire is warm and welcoming.” The old woman nodded gratefully, but as they walked deeper into the woods, the trees closed in around them, and the village lights began to fade.

A strange chill filled the air, making Hana shiver. “Why do the woods feel so strange?” she asked, feeling more uneasy.

Then, she heard a low, eerie laughter—like the sound of crackling embers. The woman’s form began to shift; her robes fell away like a snake shedding its skin, revealing thin, blue-veined limbs.

Her head split open, and her mouth stretched wide in a terrifying grin—sharp teeth glistened, and her tongue flicked like a serpent. “Because unfulfilled promises make me hungry for betrothed girls!”

Agubanba lunged at Hana, her claws tearing through Hana’s obi (a traditional sash), pinning her to the ground. Hana caught a whiff of the creature’s foul breath and glimpsed the distant flames of her village, a reminder of her freedom. In desperation, she grabbed a handful of moss and hurled it into Agubanba’s gaping mouth, hoping to choke the beast.

With a gagging sound, the old woman loosened her grip, and Hana took off running, the underbrush tearing at her skin and her lungs burning with each breath. Behind her, the creature chased on, moving faster and faster, its claws swiping at the air.

Reaching the edge of a stream, Hana plunged her hands into the cold water, scooping up stones and chanting: “Waters cleanse, blind one flee; let stone and stream hold you back!” She flung the pebbles behind her, hitting the crone and forcing her to retreat with a startled yelp.

As dawn broke and painted the pines gold, Hana stumbled home, her basket empty and her spirit weary. The betrothal still took place, but Hana’s songs became somber, echoing the warnings she had heard in every rustle of leaves—her scar now a reminder of the price of mercy.

You may also enjoy:

Mara: The Buddhist Demon King of Desire and Death

October 13, 2025

Who Was Abezethibou, the Fallen Angel Who Opposed Moses?

October 1, 2025

Iblis, the Jinn King of Darkness and Deception

September 29, 2025

Amdusias in the Ars Goetia: The Demon of Dark Music

December 2, 2025

Who Is the Demon Andras, The Great Marquis of Discord?

January 15, 2026

Lamashtu, the Mesopotamian Demoness of Childbirth and Infant Death

November 4, 2025

Hearthbound Vengeance in Iwate’s Forsaken Hamlet

In the remote villages of Iwate, where the rain never seemed to stop and thatched roofs sagged under the weight of moisture, lived a group of women known as hearth-keepers. These women dedicated their lives to keeping the fire alive in their homes, even as the darkness around them grew.

Among them was Miko, an eighteen-year-old girl who cared for her ailing mother with unwavering devotion. Her mother often whispered about eerie beings made of ash, warning her, “Don’t disturb the quiet, my child; it might awaken Agubanba, the blind reaper of the young.”

Miko listened but couldn’t help feeling curious; on stormy nights, she would poke the glowing embers, imagining the strange shapes they formed—perhaps tiny faces or fleeting thoughts.

Winter arrived early that year, wrapping their home in snow and isolating them as if in a tomb. Miko’s mother became gravely ill, her breath growing weak. In her desperation, Miko rummaged through the hearth for glowing embers to make healing teas.

As she dug through layers of soot built up over the years, she accidentally stirred something magic awake. Suddenly, a strange voice filled the air, asking, “Who is disturbing my rest?” Miko froze in fear as a terrifying figure appeared—a haggard old woman with eyes as dark as night, dressed in a kimono that seemed to be made of ashes.

Panic rushed through Miko. The old woman leaned closer, sniffing the air like a predator. “You’re young and full of life; your warmth will ease my endless cold.”

With long claws extended, she reached out, but Miko quickly scattered the coals, sending sparks flying. The hag moved closer, her mouth opening wide as she prepared to strike. In that moment, Miko heard her mother’s weak voice shout, “Salt, child—put salt at the door!”

Driven by fear, Miko grabbed a container of salt and threw it into the air. It hit the old woman, causing her to scream in pain as her flesh bubbled as if scalded.

The sound shook the very walls of their home. Agubanba, feeling the sting, grew furious and used the ashes around her to create a blinding cloud, trying to overwhelm Miko. “Join me in eternal darkness!” she shouted as she lunged forward.

With her vision blurred and her heart racing, Miko grabbed a metal poker, still warm from the forge, and thrust it right into the hag’s shoulder, pinning her against the wall. Fire eagerly consumed the old woman’s rags as she writhed in agony, slowly disappearing into wisps of smoke. When the flames died down, all that remained was a faint outline where she had stood.

As dawn broke, Miko’s mother began to recover, crediting her daughter’s bravery for the miracle. From that day on, the hearth burned bright and clean, free from any disturbances.

Agubanba Powers and Abilities

Agubanba is a cunning and dangerous creature known for her unique powers, which allow her to manipulate her surroundings and take advantage of them.

Although she is blind, her other senses are incredibly sharp—especially her hearing, which lets her detect heartbeats from a distance. She can even imitate the voices of loved ones, using this skill to draw her victims in and make them feel at ease, only to trap them when they least expect it.

Her abilities center around ash, which she can control to create blinding clouds or illusions of herself, confusing groups of people and isolating her chosen target.

Moreover, while her bite isn’t just painful, it injects a paralyzing venom that can render her victims helpless, leading to a state of “ash-sleep” where they awaken to find only bones left behind.

In relation to other creatures in the yōkai world, Agubanba is somewhat in the middle—she may not be as strong as massive oni. Still, she is far cleverer than the water-dwelling kappa and stealthier than flying tengu in close quarters.

Against her mountain witch relatives, she may not have the strength to devour them, but she excels at sneaking into homes where they struggle.

Agubanba can strike at any time of year, although she does have some weaknesses, particularly when it comes to fire. In battles with other yōkai, she can use her ash storms to disrupt flying enemies.

Some of Agubanba’s powers and abilities include:

- Ash Manipulation: Conjures blinding clouds or binding tendrils from nearby soot, obscuring escape routes or entangling limbs.

- Vocal Mimicry: Imitates familiar voices with flawless inflection, drawing victims into ambushes; range extends to echoing cries across valleys.

- Enhanced Senses: Blindness heightens the senses of smell and hearing, allowing individuals to detect fear-sweat or pulse-quicken up to 50 meters away, and navigate fog or darkness flawlessly.

- Paralytic Bite: The cranial maw injects a numbing toxin via its fangs, immobilizing prey for leisurely consumption; the effects last for hours, mimicking sleep.

- Illusory Deception: Projects false images of frail elders or lost children from shadows, exploiting empathy to close distances undetected.

- Rapid Regeneration: Reforms from ash remnants if “killed,” requiring total dispersal by fire or salt to banish temporarily.

How to Defend Against Agubanba

The Japanese lore is filled with practical advice on how to protect against Agubanba.

One of this creature’s main weaknesses is her connection to ashes, so keeping your home clean and pure can help keep her at bay.

Salt, which is important in Shinto purification rituals, plays a key role in defense. By creating a circle of salt around a firepit or doorway and saying a special phrase (“Hai no onryō, modore!”), you can cause her to dissolve into harmless dust upon contact.

Using iron tools amplifies these defenses; for example, striking a metal poker against an anvil or scattering iron nails can create barriers that repel her.

Interestingly, fire can help protect against her, too—though she may come from ashes, a strong and sustained fire can burn her away. Throwing lanterns or starting bonfires during her nighttime wanderings can prevent her from returning, as her ash-like form can’t hold together in the flames.

Traditional chants and songs passed down through generations can also disrupt her false appearances. Singing repetitive phrases (like “Namu Amida Butsu” or folk songs like “Akai hi o harau, gu-ban o harau”) can reveal her true nature.

For those traveling, having reflective surfaces (such as mirrors or polished knives) can confuse her. When she sees her “reflection,” she can become paralyzed, giving you time to escape.

Leaving offerings like rice balls mixed with wasabi at crossroads can help calm her hunger and keep you safe. Still, it’s advised not to become too reliant on them, as that might draw her closer.

Agubanba vs Other Yōkai

| Name | Category of Yōkai | Origin | Threat Level | Escape Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamauba | Obake (witch) | Exiled human women transformed by mountain isolation into cannibalistic crones | High—ambushes travelers with deceptive hospitality | Medium; evasion via flattery or swift descent from heights, but her terrain mastery prolongs chases |

| Oni | Akuma (demon) | Cursed warriors or natural disasters personified as horned brutes | Extreme—raw strength crushes villages wholesale | High; requires divine artifacts or heroic alliances, as brute force overwhelms most flight attempts |

| Kappa | Mizuchi (water imp) | River spirits born from drowned children, gaining reptilian form | Medium—drowns or disembowels with cunning traps | Low; spilling its water dish via distraction causes instant weakness and retreat |

| Tengu | Daitengu (bird demon) | Fallen monks or arrogant swordsmen ascending to winged humanoids | Variable—storms ravage forests, but mentors warriors | Medium; humility and riddle-solving appease, though aerial pursuits demand clever ground cover |

| Kuchisake-onna | Onryō (vengeful ghost) | Jealous wife mutilated by husband, haunting as masked slasher | High—urban ambushes with surgical shears | Medium; evasive answers (“average”) confuse her, allowing urban crowds for blending escape |

| Futakuchi-onna | Obake (two-mouthed woman) | Neglectful gluttons sprouting back-mouths from guilt-fueled curses | Medium—drains household resources via hidden feeding | Low; satisfying the rear maw with food halts aggression, turning her into reluctant ally |

| Rokurokubi | Bakemono (shapeshifter) | Cursed women extending necks nocturnally to spy or strangle | Low to medium—voyeuristic peeks escalate to nocturnal attacks | Low; dawn forces retraction, and binding hair with cords prevents elongation |

| Noppera-bō | Yūrei (faceless ghost) | Trauma victims erasing features to instill existential horror | Low—psychological terror via blank stares | Low; polite dismissal scatters it, as confrontation amplifies manifestations |

| Nurarihyon | Yōkai lord | Ancient house-invaders evolving into slippery patriarchs | High—commands lesser spirits, infiltrating homes subtly | High; exorcism demands full household unity, as it slips away only after total banishment rites |

| Gashadokuro | Oni (giant skeleton) | Massacred souls amalgamating into colossal undead | Extreme—rattling bites sever heads silently | High; fleeing en masse confounds it, but solitary encounters end in instant decapitation |

| Yuki-onna | Yūrei (snow woman) | Blizzard fatalities manifesting as pale seductresses | High—freezes victims in blizzards with icy kisses | Medium; averting gaze and warmth sources melt her grasp, though seduction lures into peril |

| Karasu-tengu | Kotengu (crow demon) | Corvid spirits gaining humanoid cunning from battlefield dead | Medium—harries with beak strikes and wind gusts | Medium; offerings of mirrors flatter vanity, grounding flights for evasion |

| Akaname | Yokai (licker) | Filth-born cleaners turned invasive hygiene obsessives | Low—licks clean but induces illness via unclean tongues | Low; spotless baths deter visits, transforming threat into unwitting sanitation aid |

Symbolism

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Element | Earth—ash and soil as base, embodying grounded decay and hearth-bound entrapment |

| Animal | Rat—scuttling in shadows, gnawing unseen; her stealth mirrors vermin incursions into homes |

| Cardinal Direction | North—Tohoku’s frozen climes, aligned with Onmyōdō’s wintry demons of isolation |

| Color | Gray—soot’s pallor, symbolizing blindness and the monotonous dread of rural neglect |

| Plant | Mugwort—burned in purification rites to ward her, its bitter smoke repelling ash affinity |

| Season | Winter—blizzards seal hamlets, amplifying hearth reliance and her emergent pangs |

| Symbolic Item | Iron poker—tool for stirring fires turned weapon, representing vigilant domestic defense |

In Japanese culture, Agubanba symbolizes the undercurrents of matriarchal anxiety and communal fragility.

Her blind predation is an allegory for adolescence’s perils—when girls, stepping from sheltered hearths into broader worlds, risk erasure by unseen societal maws.

She embodies the taboo of elder neglect: in aging Tohoku villages, where demographics skew gray, her ravenous form indicts the cost of isolation, urging filial bonds lest resentment birth monsters from mundane ashes.

Festivals like Akita’s Namahage—wild oni-mummers scaring children straight—echo her in reverse: communal rituals that exorcise neglect through noise and fire, ensuring hearths remain shared sanctuaries.

You may also enjoy:

Allocer: Great Duke of Hell and the 52nd Spirit of the Ars Goetia

November 17, 2025

The Kumbhanda: Grotesque Demons of Buddhist Hell

November 13, 2025

Amaymon: The Infernal King Who Commands Death and Decay

November 17, 2025

Who Is Adrammelech in Demonology and the Bible?

October 1, 2025

What Is Akaname, The Filth-Licking Yōkai?

October 28, 2025

Who Was Abezethibou, the Fallen Angel Who Opposed Moses?

October 1, 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Agubanba?

Agubanba is a blind, cannibalistic female yōkai from Japanese folklore, primarily associated with Akita and Aomori Prefectures in northern Japan. Known also as “Ash Baldy” due to its name meaning “gray monk,” it emerges from piles of ash in hearths and targets young women who have recently come of age, luring them with deceptive calls before devouring them.

Where does Agubanba come from?

Agubanba originates in the folklore of the Tohoku region of Japan, particularly Akita and Aomori, where stories date back at least to the Edo period.

What does Agubanba look like?

Agubanba appears as an elderly hag with milky-white. These cataract-covered eyes render her completely blind, long, disheveled hair matted with ash, and tattered robes resembling a monk’s garb, stained gray with soot. Her most striking feature is a large, gaping mouth located on the top of her head, used for consuming victims whole.

How does Agubanba hunt its victims?

Agubanba preys on young women by mimicking the voices of their family members or children in distress, calling out from the hearth to draw them close under the pretense of needing help. Once lured, it seizes them with claw-like hands and swallows them headfirst into its head-top mouth, cooking the remains in the family fire for sustenance.

Is Agubanba related to Yamauba?

Yes, Agubanba shares similarities with the Yamauba, another mountain-dwelling hag yōkai known for cannibalism, but differs in habitat and appearance—Yamauba lives in remote forests while Agubanba haunts household hearths. Both target vulnerable young females and represent societal anxieties about aging women and isolation. Yet Agubanba’s ash origin and head-mouth set it apart as a more domestic, insidious variant.

Why does Agubanba have a mouth on its head?

The mouth on Agubanba’s head allows it to consume prey discreetly while feigning normalcy, swallowing victims upside-down to muffle screams and integrate remains into the fire. This grotesque adaptation stems from folklore equating ash play with inviting chaos, where the inverted maw mirrors the hearth’s flames licking upward.

Is Agubanba real?

Agubanba is not a real entity but a yōkai from Japanese oral traditions, used to explain unexplained disappearances or fire mishaps in isolated northern villages. Its “reality” lies in cultural psychology, manifesting fears of blindness, aging, and matriarchal abandonment during feudal eras.