Yaksha (Sanskrit: y akṣa; Pali: yakkha) are a fascinating group of supernatural beings found in Buddhist beliefs. They represent a mix of good and mischievous traits, reflecting the balance of nature in our world.

Often associated with forests, rivers, and hidden treasures, these nature spirits are seen as guardians of the earth’s resources, helping to bring fertility and prosperity. However, they can also be playful, sometimes causing storms or tricking people.

In Buddhist stories, Yaksha often serve as assistants to more powerful gods (like Vaiśravaṇa) who protect the northern direction.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Yaksha (Sanskrit), Yakkha (Pali), Yèchā (Chinese), Yasha (Japanese), Gnod sbyin (Tibetan), Yak (Thai) |

| Title | King of Yakshas: Vaiśravaṇa (or Kubera); Heavenly Generals: Twelve Yaksha protectors of Bhaiṣajyaguru |

| Region | India, Sri Lanka, Tibet, China, Japan, Thailand, Southeast Asia |

| Type | Buddhist nature spirit, guardian deity, occasionally demonic entity |

| Gender | Male (Yaksha); female counterparts: Yakshini or Yakkhini |

| Realm | Desire realm; earthly wilderness, forests, waters; northern quarter of Mount Sumeru |

| Obstacle/Threat | Mischievous illusions, tempests, or cannibalistic attacks on travelers; karmic tests of virtue |

| Associated Figures | Buddha, Vaiśravaṇa, Hariti (Yakshini), Vajrapani (as Yaksha form), Rakshasas |

| Weapon/Item | Club (gada), staff, or treasure purse; lotus or yak-tail flywhisk for guardians |

| Weaknesses | Dharma teachings, mantras, meditation; conversion through sermons leading to protection |

| Associated Deity/Figure | Gautama Buddha (converts malevolent ones); Bhaiṣajyaguru (Medicine Buddha, guarded by Twelve Yaksha) |

| Pantheon | Buddhist (Theravada, Mahayana, Vajrayana) with Hindu and Jain influences |

| Primary Sources | Pali Canon (Samyutta Nikaya, Jataka Tales), Lotus Sutra, Avatamsaka Sutra, Lankavatara Sutra |

Who or What is a Yaksha?

In Buddhist traditions, a Yaksha represents the mysterious and vibrant spirit of nature—a guardian who both helps and tests humanity. These beings exist in the spaces between the known and unknown, often seen in ancient forests, hidden mountain springs, or deep within the earth where treasures lie.

Unlike the clearly evil beings called Asuras, Yakshas act as moral guides. They often change their ways after meeting enlightened beings, transforming from potential adversaries into protectors of spiritual truths.

“Yaksha” Meaning

The term “Yaksha” comes from ancient Sanskrit and evokes images of swift, dreamlike beings that are connected to the hidden rhythms of the earth.

The name likely originates from the Vedic word “yakṣ,” which means “to worship,” “to honor,” or “swift ray of light.” This suggests that Yakshas are bright spirits serving as links between our everyday world and the divine, similar to how sunlight flickers through leaves or water flows quickly in streams.

In a related language called Pali, it is referred to as “yakkha,” which also relates to sacrificial offerings. This connection suggests that Yakshas play a role in rituals intended to appease them.

Over time, these beings transformed from pre-Buddhist nature spirits mentioned in ancient hymns that were called upon for fertility and rain into figures within Buddhism that represent the echoes of human desires and karma.

Across various Asian cultures, the concept of Yaksha has adapted and changed. For example, in Tibetan Buddhism, they are known as “gnod sbyin,” which translates to “harm-giver.” In Chinese Buddhism, they are called “yèchā” (夜叉), or “night fork,” suggesting trickster figures who navigate between danger and enlightenment.

In Japan, they became known as “yasha,” depicted as powerful warriors resembling demons in temple art. Still, they can also find redemption through the grace of the Buddha.

In Thailand, they are referred to as “yak” (ยักษ์), and are often portrayed as large, friendly guardians in folklore, especially in stories like “Phra Aphai Mani,” where they gather treasures but ultimately yield to bravery and moral goodness.

How to Pronounce “Yaksha” in English

The term “Yaksha” can be pronounced in a few different ways depending on the language.

In English, it’s usually said like “YAHK-shuh,” where the first part sounds like “yacht” without the ‘t,’ and it’s followed by a soft ‘sh’ sound, like in “shush.”

In Pali, another language, it’s pronounced “YAHK-khah,” which features a longer ‘kh’ sound that resembles a gentle throat clearing.

When you look at the Chinese version, “yèchā,” it’s said as “YEH-chah,” with the first part rising in tone and the second part falling.

In Japanese, the word becomes “yasha,” pronounced as “YAH-shah,” which sounds clear and strong.

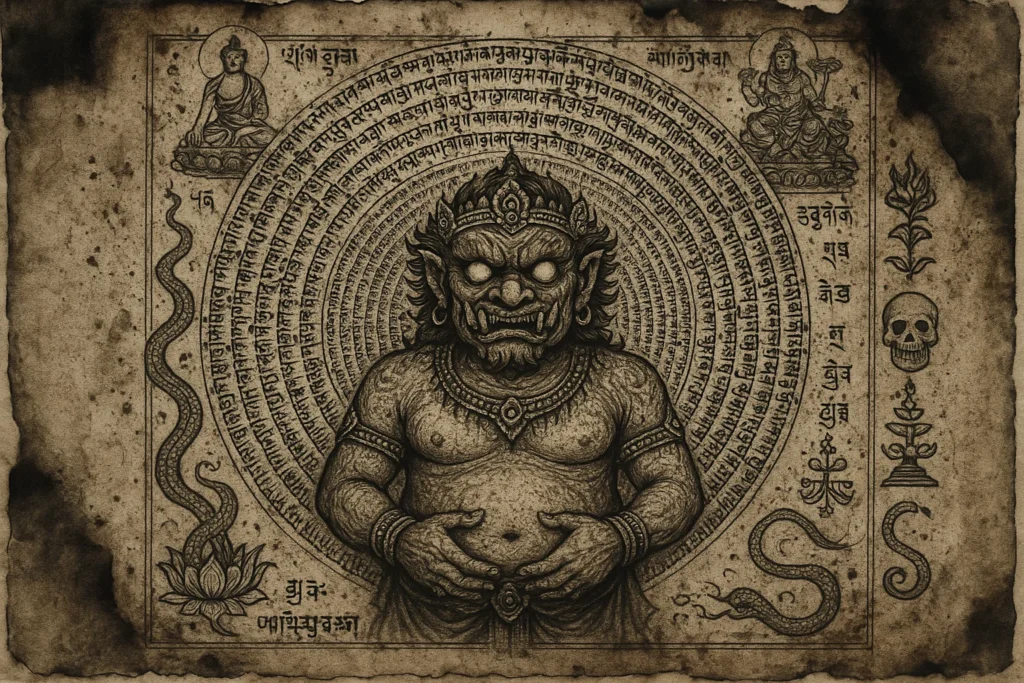

What Does a Yaksha Look Like?

Yakshas typically show a mix of human-like qualities and wild, untamed energy.

In some of the oldest Indian carvings (like those from the Bharhut stupa dating back to the 2nd century BCE), male Yakshas are depicted as short, sturdy guardians. They have strong bodies that represent the richness of the earth, and their skin colors can range from earthy browns to vibrant greens.

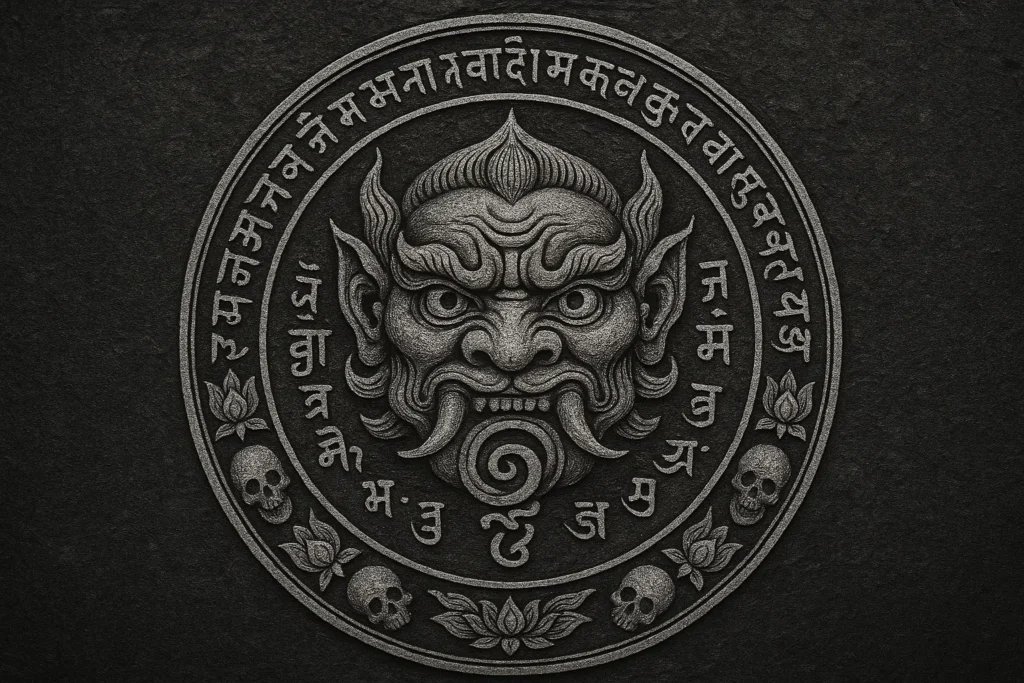

These figures often have lively yet serious faces, with wide eyes full of watchfulness, noticeable noses, and mysterious smiles that show off shiny, pearl-like teeth. Decorated with flower garlands, snake-like arm jewelry, and crowns covered in jewels, they often hold clubs or overflowing bags of gems and stand in dynamic poses that resemble the trees they protect.

On the other hand, female Yakshas (known as Yakshinis) have a different vibe—they radiate charm and liveliness with graceful, curvy bodies, flowing hair, lotus flowers in their hands, and delicate veils that cling to their figures. They embody the spirit of nurturing, similar to the exquisite Didarganj Yakshi sculpture from the 3rd century BCE.

In Theravada traditions—which are mainly found in Sri Lanka and Thailand—Yakshas take on a more fearsome appearance, often portrayed as large, frightening creatures with rugged fur, sharp tusks, and claws ready to pounce.

A legendary figure, Silesaloma, exemplifies this image, looking scary with tangled hair and glowing eyes. However, there is a softer side: guardian Yakshas at temple entrances, like those seen in Ayutthaya ceramics from the 14th to 16th centuries, have friendly figures and raised hands, calming any fears with their peaceful presence.

In Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, Yakshas become even more spectacular.

In Tibetan artwork, they transform into armored protectors, fierce warriors with many arms and colorful blue skin marked with bold patterns. One, named Vajrapani, is shown wielding thunderbolts in powerful scenes.

Meanwhile, in Chinese and Japanese art (like Dunhuang murals and statues in Kyoto), Yakshas appear as more ethereal, elegant figures dressed in flowing robes, with sly eyes. These artists depict them as guardians of the Medicine Buddha, where warrior-like figures hold lances and snakes, blending fierceness with grace.

Origins

The story of Yaksha begins in the ancient spiritual traditions of India, long before Buddhism emerged. It can be traced back to the Vedic texts (such as the Rigveda, dated around 1500 BCE), where Yaksha are described as mysterious beings or “swift ones.” These spirits were often honored alongside forest nymphs to ensure good harvests and safe journeys through nature.

Scholars suggest that the concept of Yaksha may have roots in earlier tribal beliefs, possibly linked to indigenous deities who were protectors of sacred groves, eventually evolving into guardians in Hindu mythology.

In Hindu texts like the Mahabharata, Yaksha are depicted with moral complexity: they can be kind to the virtuous but are also capable of punishing the wicked. One notable story features a Yaksha testing the hero Yudhishthira’s understanding of righteousness through thought-provoking riddles.

However, when Buddhism arose around the 5th century BCE, it took these ancient ideas and transformed them. As a result, in Buddhist teachings—especially in the Pali Canon compiled after the Buddha’s time—Yaksha appear in a different light, representing the struggle between desire and enlightenment.

The tales of the Jataka—which recount the previous lives of the Buddha—further explore this theme, portraying encounters with menacing Yaksha that highlight virtues like wisdom and compassion.

As Buddhism spread across Central Asia with the support of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, Yaksha absorbed influences from other cultures, merging with local legends. In this way, they became fierce protectors, blending elements from various traditions.

By the Common Era, in Mahayana Buddhism, texts like the Lotus and Avatamsaka reframed Yaksha as divine allies, now seen as powerful protectors against illness and negativity. In Tibetan Buddhism (which started developing around the 8th century), these beings were integrated into spiritual practices to help overcome obstacles.

As Buddhism traveled along trade routes to China and Japan, Yaksha adapted once again. In Chinese texts, they became earth guardians promoting harmony, while in Japan, they were portrayed more negatively as storm-bringers but could still be redeemed through spiritual challenges.

You may also enjoy:

What Is the Akkorokamui, Japan’s Colossal Sea Monster?

November 14, 2025

Who Is Abalam in Demonology? The Terrifying King That Serves Paimon

September 30, 2025

Akateko: The Bloody Hand Ghost That Guards a Cursed Temple Tree

November 14, 2025

Nasnas: The Monstrous Demon Hybrid That Haunted Pre-Human Earth

November 12, 2025

Edimmu: The Mesopotamian Wind Demon That Steals Life

November 6, 2025

Abura-sumashi: The Potato-Headed Yōkai That Punishes Greed

October 23, 2025

Regional Variations

Different Buddhist traditions have their own unique ways of depicting Yakshas. For example, in the Theravada tradition, Yakshas are often seen as down-to-earth figures focused on moral lessons.

In contrast, the Vajrayana portrays them as more mystical warriors with secret knowledge. Despite these differences, all Yaksha representations share common themes of protection and unpredictability, allowing them to connect with local beliefs and customs.

| Region/Tradition | Appearance | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Theravada Thailand | Towering ogres with tusked grins, fur cloaks, and gem purses; pot-bellied and green-skinned. | Temple guardians warding forests; tricksters in folktales testing generosity. |

| Mahayana China | Slender, armored generals with serpentine coils and luminous halos; porcelain-pale with flowing robes. | Protectors of Medicine Buddha; enforcers against disease and doctrinal foes. |

| Vajrayana Tibet | Wrathful multi-armed figures in azure fury, horned crowns aflame; dwarfish yet colossal in thangkas. | Dharmapalas subduing inner demons; oath-bound allies in tantric rites. |

| Mahayana Japan | Oni-like yasha with wild manes, fangs bared in snarls; red-skinned warriors trammeled under Bishamonten’s foot. | Fierce servants of heavenly kings; metaphors for tamed passions in Zen koans. |

| Theravada Sri Lanka | Grotesque yakkhas with matted locks and claw-tipped limbs; shadowy, bat-winged in cave murals. | Haunters of wilderness; converts via Buddha’s words, embodying karmic rebirth. |

Buddhist Cosmology

In Buddhist beliefs, Yaksha are spirit beings that live in a realm focused on desires (the lowest of three spiritual levels). This place is full of sensory pleasures, though these pleasures are temporary and often lead to difficulties.

Yaksha are believed to reside near the northern side of a sacred mountain called Mount Sumeru, close to the palace of Vaiśravaṇa. They serve as connections between humans and divine beings, playing an important role in balancing good and bad actions.

There are two types of Yaksha. The benevolent ones help maintain nature (like taking care of groves and rivers, which creates good karma and allows people to be reborn in better circumstances). On the other hand, the more harmful Yaksha—often driven by greed or anger—act like ghouls, preying on those who stray from the path.

Additionally, some Yaksha reside in Trayastriṃśa Heaven, the realm of Indra, where they belong to a group of eight protective armies. They participate in teachings from the Buddha and commit to safeguarding against temptations and false beliefs.

Yaksha in the Pali Canon

In the Pali Canon, Yakshas are depicted as figures that inhabit wild and untamed places. They often represent negative thoughts and emotions that can trouble the mind. The Buddha is said to have tamed these beings with his wisdom, transforming them into allies who support the teachings of Dharma, or the path of truth.

| Source | Quote |

|---|---|

| Samyutta Nikaya 10.3 (Alavaka Sutta) | “Then the yakkha Alavaka, taking hold of the young bhikkhu by the throat and hurling him down from the platform, vanished. Then the yakkha Alavaka, at sunrise, went to the monastery gate, and striking it with his hand, he caused it to crash, and entering, he said: ‘Come out, you recluse! Where is that recluse?'” (Pali: *”Atha kho āḷavako yakkho purisapiṇḍena gāḷhabandhanaṃ gahetvā mañcā orabhitvā antaradhāyi. Atha kho āḷavako yakkho pubbaṇhasamayaṃ vihāradvāraṃ pāvisiṃsu hatthena akkhantvā paviṭṭhā: ‘forth come, ascetic! Where is that ascetic?'”) |

| Samyutta Nikaya 10.7 (Sakka Sutta) | “The yakkha said: ‘Who is this monk who comes to our haunt? We shall give him a thunderbolt!’ But Sakka, king of gods, replied: ‘Do not harm him, for he is the Tathagata’s son.'” |

| Samyutta Nikaya 10.8 (Sanjiva Sutta) | “Then the yakkha Sanjiva, in the body of a serpent, coiled around the monk, but the monk’s mindfulness prevailed, and the yakkha uncoiled, ashamed.” |

| Jataka Tales No. 522 (Vidhurapandita Jataka) | “The yakkha-king Vessavanaña, disguised as a wanderer, tested the prince with riddles profound; answered wisely, the yakkha bowed low, granting boons untold.” (From commentary: Pali excerpt on yakkha interrogation.) |

Yaksha in Mahayana Sutras

Mahayana sutras elevate Yaksha to celestial stature—fierce yet enlightened protectors who, once demonic, pledge eternal vigilance to the Buddha’s teachings.

| Source | Quote |

|---|---|

| Lotus Sutra, Chapter 26 | “The twelve yaksha generals, with one mind and mouth, declare to the Buddha: ‘We too, in this manner, will protect and guard all who keep the sutra, so that no one shall injure them, and they shall be free from all illness and untimely death.'” |

| Avatamsaka Sutra, Chapter 40 | “Yaksha kings, with their retinues, assemble in the vast assembly; they venerate the Buddha, offering jewels and praises, and vow to shield the Dharma from maras’ grasp.” |

| Lankavatara Sutra, Chapter 10 | Ravana, overlord of yakshas, approaches the Buddha: ‘Reveal the truth of mind-only, that illusions cease.’ Thus, the yaksha king attains the wisdom of non-duality. |

| Ksitigarbha Sutra, Chapter 12 | “In hells profound, yaksha tormentors wield iron tools on sinners; yet hearing Ksitigarbha’s vows, they repent, becoming guardians of the vow-keepers.” |

Powers and Abilities

In terms of raw power, Yakshas are, once again, quite unique. They stand somewhere between powerful cosmic beings and lesser spirits. While they’re not as all-powerful as Buddhas or the great warlords of the Asuras, they are definitely stronger than the troubled spirits known as Pretas or the regular Nagas.

Yakshas are fierce like the Rakshasas—known for their ability to cause great destruction. Still, they are also tied to the earth and don’t possess the vast illusions of Mara or the flying skills of the Garudas.

Here are some of their notable abilities:

- Illusion-Crafting: Yakshas can create mirages, such as fake oases or feasts, to trick and confuse travelers. In ancient texts, they are described as able to create entire deceptive worlds based on what their victims desire.

- Shape-Shifting: They can transform into different forms, from charming maidens (known as Yakshinis) to enormous ogres. Some traditions even describe them taking on more complex forms for special rituals.

- Elemental Control: Yakshas can summon storms, floods, or earthquakes to protect their treasures or punish those who intrude upon them.

- Treasure Guardians: They can discover or hide valuable riches underground. Some Yakshas are known to reward those who do good deeds with wealth.

- Physical Strength: They possess incredible physical power, capable of uprooting trees or overpowering enemies. Stories often show them capturing heroes with their powerful grips.

- Telepathy and Riddles: Yakshas can read minds to find weaknesses and challenge individuals with difficult moral puzzles, often testing their wisdom.

- Conversion Immunity: If they are subdued by teachings, they gain long-lasting life and healing abilities, serving as loyal protectors of the Dharma.

- Healing Presence: Acting as followers of the healing Buddha, they can help relieve ailments through special chants, drawing on the life forces of nature.

Yaksha Myths, Legends, and Stories

The Yaksha Alavaka

In the lush outskirts of Vesali, there lived a fierce creature named Alavaka, a yakkha who made life miserable for travelers. He could be found at an old, stormy shrine where he would demand challenges from anyone who wandered too close. If they failed, he would devour them.

Alavaka was a terrifying figure, lurking in the shadows with eyes filled with a fierce hunger. His thunderous roars could shake the ground and scare away animals. Each week, he captured seven monks, dragging them away without a trace, leaving only whispers of their fate.

One day, the Buddha, calm in the face of danger, sent his devoted follower, Meghiya, to confront Alavaka. However, as soon as Meghiya approached, the yakkha attacked.

With a powerful grip, he threw the monk away into the thorny bushes, bellowing loud enough that even the sunrise seemed to pause. “Come out, you monk! Who dares to enter my territory?”

His booming voice scared the birds into flight and uprooted young trees. But Meghiya, though hurt, returned bravely and began to speak about how all things change, as if sending shafts of light into Alavaka’s anger.

Furious, Alavaka lunged at Meghiya three times over several days, trying to scare him away with his massive form and grinding tusks.

“Run, or you will be destroyed!” he roared, his wild hair whipping in the wind.

Still, the monk remained steadfast, calming the raging spirit with words of wisdom: “Everything that has a beginning will end; life’s pleasures are temporary, just like foam on the waves.”

By the third evening, Alavaka was growing tired; his fierce claws retracted, and he stared down in shame, like dark clouds gathering before a storm.

Then, the Buddha himself appeared, shining with a light brighter than the full moon. Humbled, Alavaka no longer snarled but asked, “Why have you come to my dark kingdom, wise one?”

Sitting gracefully, the Buddha shared teachings about letting go of desires, understanding the cycle of our actions, and finding true peace.

“What is real wealth?” the yakkha wondered, his voice softening. “It’s not gold or riches; it’s the light of kindness and good deeds,” the Buddha explained, helping to dissolve Alavaka’s misconceptions one by one.

Transformed by this newfound understanding, Alavaka shed his terrifying form and donned robes of gentleness. No longer driven by hunger, he promised to protect the Buddha’s followers: “Let me guard you from the traps of temptation, just as tree roots hold onto the ground.”

The once-feared creature became Alavaka the Protector, and his shrine turned into a place of hope where pilgrims would seek his guidance in facing their personal challenges. In the world beyond, other yakkhas heard this story and began to learn that compassion is far more powerful than mere ferocity.

Silesaloma, The Sticky-Haired Demon

In the rugged mountains of Himavat, where the mist hangs low and the pine trees reach for the sky, there lived a fearsome creature named Silesaloma. He was a yakkha, a being known for his wicked ways, with a body covered in sticky bristles that trapped anyone who dared come too close.

Silesaloma towered like a palm tree, his fur shiny and messy under the moonlight. His sharp teeth stuck out from his fierce mouth, and his eyes glowed with greed. People told stories of traders who disappeared completely, captured by Silesaloma as he devoured them, their cries silent as he crunched their bones.

Young Prince Jambuka, courageous but kind-hearted—a hero in every sense—set out to put an end to this creature’s terror. He didn’t carry just a sword; he brought a bow, a spear, a shield, and a magic charm.

“This monster will fall by my bravery,” he declared to his family as he left during twilight. The path to Silesaloma’s lair was dangerous—steep cliffs gaped open like giant mouths, and the wind howled like a sad song—until morning light revealed a cave that reeked of decay.

Silesaloma stirred, sensing new prey. “Come closer, young prince, and prepare to be my next meal!” he roared, his voice echoing like a landslide. Jambuka shot arrows first, but they just stuck in Silesaloma’s tough skin like flies in honey.

Next, he threw spears with all his strength, but they got stuck too, making the yakkha laugh even harder. Jambuka swung his sword, but it got caught in the thick fur of the beast as he tried to cut through.

Desperate now, Jambuka used his heavy shield to strike the demon’s head, cracking one of its horns, but getting his arm stuck to the monster.

At the end of his wits, he called upon his magic charm and recited a verse of truth: “Through kindness, not violence, can chains be broken; harm only comes back to those who cause it.”

His words sparked a bright light inside him, and Silesaloma writhed in pain as his malice was consumed by the warmth of kindness. “What magic is this?” the yakkha gasped as he shrank in size, his fur turning to ashes.

“It’s not magic, it’s the power of kindness,” replied Jambuka, freeing himself without harming the creature.

Moved by Jambuka’s compassion—no desire for revenge, just a wish to help—Silesaloma knelt down, realizing the error of his greedy ways. “I once feasted on the greed of others, but now I see the value in virtue. Please, teach me your way,” he asked Jambuka.

The prince spoke about the joy of giving, the protection in non-violence, and the light of understanding; Silesaloma, now wiser, promised to protect the forest instead of destroying it, helping lost travelers instead of trapping them.

You may also enjoy:

Lamia: The Queen Cursed to Devour the Children of Others

January 7, 2026

Who Is Shiva, the Destroyer and the Lord of the Universe?

November 12, 2025

Abura-akago: The Oil-Licking Demon Baby

October 22, 2025

Who Were the Hinn, the First Spirits of Creation?

November 12, 2025

Who Is Ambolin, the Demon of Nighttime Dread

December 1, 2025

Si’la: The Seductive Jinn Who Lures Travelers to Their Doom

October 9, 2025

Ravana’s Plea

In the enchanting land of Lanka, filled with lush greenery and vibrant coral, there ruled Ravana, the powerful king of the yakkhas. His palace was a maze of stunning towers made of pearl and gold, where treasures seemed to whisper secrets to anyone who would listen.

Ravana was a striking figure with ten heads and twenty arms, capable of playing music and wielding swords in a captivating dance. He was wise, with fiery eyes and a voice that could echo like thunder while still holding a melody.

Although he had conquered many lands and written beautiful hymns in praise of the god Shiva, he still felt an insatiable desire for the deepest truth, one that remained hidden from him even in his vast knowledge.

One day, news reached him about the arrival of the Buddha, a wandering sage known for his ability to see through illusions and teach profound truths that could break down the barriers of the ego. “This wise man reveals the vast ocean of the mind,” Ravana thought, and he soon sent messengers across the seas to learn more.

However, he was aware that his court, filled with magical beings who often pretended to be something they were not, scoffed at the monk’s humble ways. They mocked, “What can a man in rags possibly offer us?” while enjoying lavish feasts and dazzling performances.

Despite their ridicule, Ravana decided to disguise himself as a wanderer, wearing simple clothes over his royal stature, and traveled to the mainland where the Buddha spoke.

A large crowd had gathered—deities shining brightly, serpents winding among the roots of trees, and people listening intently. Ravana blended into the crowd, his heart racing. As the Buddha shared his teachings, saying, “All things are created by the mind; don’t cling to appearances, for they are empty,” Ravana experienced a profound realization. The multiple heads he bore came together in understanding, and he found peace.

After the teachings, Ravana approached the Buddha, humbly revealing, “O Blessed One, source of compassion, I am Ravana, the king of the yakkhas. I seek to understand the true wisdom behind the stories of Lanka.”

The Buddha, unbothered by Ravana’s status, kindly encouraged him, “Speak, king of hidden depths; share your quest.”

Ravana opened his heart, sharing how his past victories felt hollow, and love was as fleeting as the monsoon rains. He expressed his desire to learn about the way to stop the cycle of suffering.

The Buddha spoke gently about concepts like emptiness and how we are not separate from each other. “Like waves merging into the ocean, so too can we dissolve into a greater understanding; do not harm others, for we are all part of the same dream.”

As the sun rose over Lanka, Ravana returned, a changed man—not a conqueror anymore, but a protector. He issued new laws of kindness, encouraging the yakkhas to give to the needy and opening his palaces to travelers. He built stupas, places of worship, where Buddha’s teachings could resonate forever.

Manibhadra’s Oath to the Medicine Buddha

In the misty valleys of Tivani, where rhododendron flowers bow beneath constant rainfall, lived Manibhadra, a great spirit known as a yaksha. He was a giant figure, covered in green skin with sparkling veins of quartz running through him.

His round belly resembled a full moon, and his fingers, thick like gnarled tree roots, held shining yellow stones. As the guardian of precious underground treasures—like sparkling rubies and cool blue sapphires—he fiercely protected them from thieves. Those who dared to steal were turned to stone, frozen in their greedy pursuit.

However, Manibhadra was also kind: to pure-hearted hermits, he revealed healing springs. He provided gems that could mend both bodies and destinies.

News of the Buddha, a healer whose reputation spread across time and space, reached these hidden depths. Moved by the tales of suffering, Manibhadra climbed to the high Vulture Peak, where gatherings filled the horizon with bodhisattvas shining like jewels and heavenly beings scattering flower petals like stars.

There, he encountered Bhaiṣajyaguru, the Medicine Buddha, who radiated a soothing blue light and offered remedies for earthly troubles.

“Lord of healing,” Manibhadra said, bowing deeply among those paying their respects, “I am the keeper of the earth’s hidden treasures. I promise to protect your followers from harm.”

The Medicine Buddha, seeing Manibhadra’s genuine heart, responded, “Stand tall, my guardian. With your eleven brothers, create a strong army; use your compassion to drive away sickness, confusion, and fear from the paths of my devotees.”

With this promise, Manibhadra called upon his powerful siblings, each as strong as mountains and adorned in beautiful patterns. Among them were Benzaiten, swift as the wind, and Idaten, unyielding as stone. They spread out into the world, with one calming sickness in fever-stricken towns.

At the same time, another shattered false beliefs, breaking them apart as easily as brittle jade. Manibhadra himself roamed the lands, sharing healing potions with those in need, enabling the blind to see again and barren women to bear children.

Through countless years, the Twelve brave spirits withstood challenges from Mara, the embodiment of temptation and obstacles, yet they remained strong. Temples were built in their honor, depicting the green guardian among bright blue backgrounds in stunning murals.

In the stories passed down through generations, Manibhadra’s influence lives on: a guiding reminder in the mines—“Do not let greed lure you, or the yaksha’s gaze will turn you to stone”—but to healers, a blessing: “Call upon the promise, and the earth’s embrace will heal all wounds.”

Thus, the Yaksha’s commitment became part of the Mahayana teachings, reminding us that even those who hoard great wealth can be transformed by the power of healing and compassion.

Yaksha vs Other Buddhist Demons

| Demon Name | Associated Obstacle/Role | Origin/Source | Key Traits/Powers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mara | Temptation and death | Pali Canon (Samyutta Nikaya) | Illusions, armies of daughters; shape-shifting to incite desire |

| Rakshasa | Cannibalism, shape-shifting | Jataka Tales, Lotus Sutra | Man-eating, deceptive forms; superhuman strength in battles |

| Preta | Hunger and greed | Abhidhamma Pitaka | Emaciated ghosts; insatiable appetites, causing famine illusions |

| Pisacha | Madness and possession | Mahayana Sutras (Lankavatara) | Flesh-eating, mind-altering whispers; invisibility in shadows |

| Kumbhanda | Deformity and lust | Tibetan Book of the Dead | Dwarf-like tempters; genital fixation, inducing moral decay |

| Naga | Poison and jealousy | Pali Canon (Cullavagga) | Serpentine guardians; venom blasts, weather control |

| Garuda | Aerial predation | Avatamsaka Sutra | Bird-demons; lightning strikes, enmity toward Nagas |

| Asura | Wrath and war | Pali Canon (Samyutta Nikaya) | Titanic warriors; eternal battles, fire-weapons |

| Kinnara | Seduction through music | Lotus Sutra | Half-human bird singers; hypnotic melodies, emotional ensnarement |

| Mahoraga | Destruction and rebirth | Mahayana Tantras | Elephantine titans; seismic quakes, regenerative hides |

| Kalakanja | Decay and disease | Shurangama Sutra | Black imps; plague-spreading, flesh-rotting curses |

| Bhuta | Haunting and unrest | Chinese Buddhist Folklore | Wandering ghosts; poltergeist phenomena, soul-binding |

| Yama | Judgment and hellfire | Pali Canon (Petavatthu) | Death’s lord; soul-weighing scales, infernal summons |

| Hayagriva | Obstacles in practice | Vajrayana Texts | Horse-headed fury; mantra disruption, wrathful tramples |

| Amanojaku | Contrariness and spite | Japanese Esoteric Buddhism | Inverted imps; wish-reversing, petty sabotages |

Mystical Correspondences

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Planet | Saturn (for guardianship and hidden depths; earthy restraint) |

| Zodiac Sign | Capricorn (earthly abundance, capricious authority) |

| Element | Earth (treasures, forests; grounding yet fertile chaos) |

| Direction | North (Vaiśravaṇa’s quarter; cool, concealed realms) |

| Color | Green (verdant groves); emerald for prosperity, ochre for wild fury |

| Number | 8 (one of eight legions; cycles of protection and caprice) |

| Crystal/Mineral | Emerald or jade (wealth manifestation); quartz for illusion-veils |

| Metal | Copper (earth’s vein, conductive to nature’s energies) |

| Herb/Plant | Lotus (purity amid mud); banyan for sacred groves |

| Animal | Elephant (strength, memory of treasures); serpent for hidden wisdom |

| Trait/Role | Guardianship with mischief; balancing nurture and trial |

Yaksha’s mystical tapestry connects the raw energy of the earth with deeper spiritual meanings. The vibrant green colors represent lush landscapes where hidden treasures await discovery. Like Saturn diligently moving along its path, these energies remind us of the importance of karma and the consequences of our actions.

The number 8 symbolizes balance in the universe, highlighting how it can be disrupted by our unpredictable choices. This prompts the use of green gems and other rituals to restore harmony and invite prosperity into our lives.

Copper vessels adorned with symbols from the north blend the ambitious spirit of Capricorn with the purity of the lotus flower, serving as tools for meditation on life’s ever-changing nature. Animals like serpents and elephants serve as powerful symbols, reminding us that wisdom may be hidden and strength runs deep.

Yaksha’s Items & Symbolism

At the heart of Yaksha artwork is the club (or gada), which is a heavy, rounded mace made from wood or decorated bronze. This club represents strong control over chaos. Its weight can crush illusions, while its rounded top symbolizes the nurturing side of the earth, reflecting a protective spirit.

Guardians like Manibhadra use this club to protect treasures, representing how our actions shape our lives—striking down greed while helping to create good deeds.

Another important symbol is the overflowing purse (known as pūrna-kumbha), which is filled with jewels and flowers. This symbolizes endless wealth and serves as a reminder of the importance of generosity and non-attachment. It teaches us that while prosperity can flow abundantly, it is meant to be shared with those who deserve it, rather than hoarded by those who are greedy.

Yak-tail flywhisks, called cāmara, and snake-shaped armlets add further meaning. The flywhisk symbolizes clarity by keeping away doubts, while the snakes represent hidden wisdom. The snake’s venom stands for life’s challenges, and shedding its skin symbolizes the chance to start anew.

You may also enjoy:

Empusa: The Blood-Drinking Wraith of Greek Mythology

November 20, 2025

Who Is Aka Manto, Japan’s Terrifying Red-Cloaked Yōkai?

October 24, 2025

Who Is Adrammelech in Demonology and the Bible?

October 1, 2025

Ammit: Devourer of the Dead in Ancient Egyptian Mythology

November 10, 2025

Bali: The Benevolent Asura King of Hindu Mythology

October 10, 2025

Ifrit: Demon of Fire Who Serves Iblis in Islamic Tradition

September 30, 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Yaksha in Buddhist mythology?

Yakshas are a type of nature spirit found in Buddhist stories. They are usually friendly guardians of natural things like forests, rivers, and treasures. However, some Yakshas can be playful or tricky, testing the good nature of people. They come from ancient Indian folklore and are mentioned in important Buddhist texts like the Pali Canon, where they sometimes change their ways and become protectors of Buddhism. Today, Yakshas are seen as symbols of harmony between nature’s gifts and its challenges, playing a role in spiritual practices in Southeast Asia.

Who are the Yakshas in Hindu mythology?

In Hindu tradition, Yakshas are considered semi-divine spirits linked to nature and wealth. They serve as helpers to Kubera, the god of riches. Yakshas show a mix of personalities—helping those who are good while punishing those who are greedy with illusions or storms. This duality is evident in stories like the Mahabharata. Female Yakshas, called Yakshinis, are seen as seductive forces of nature.

What is Yaksha Prashna in the Mahabharata?

Yaksha Prashna is a significant story in the Mahabharata, where a Yaksha, who is actually a disguised god named Yama, asks Yudhishthira, one of the heroes, a series of deep questions about right and wrong by a magical lake. If Yudhishthira answers wisely, he can bring his brothers back to life. This conversation delves into important themes like ethics, the nature of existence, and what true happiness means, showcasing Yudhishthira’s ability to judge wisely.

What are the differences between Yakshas and other mythical beings like Rakshasas?

Yakshas and Rakshasas are both supernatural beings, but they are quite different. Yakshas are often seen as protective guardians of nature, while Rakshasas are more like evil creatures that act out of anger and chaos. This contrast is clear in stories like the Jataka tales and various epics. Both can change their shapes, but Yakshas are associated with wealth and fertility, and they can be redeemed through good actions. In contrast, Rakshasas represent disorder and negativity.

Are Yakshas evil or benevolent?

Yakshas are complex characters that can be both good and bad. They can act as kind guardians who promote prosperity. Still, they can also play tricks or create chaos for those who deserve it. Their actions are often linked to the idea of karma, meaning they respond to people based on their deeds. In Buddhist teachings, overcoming a Yaksha’s challenges can lead to enlightenment.