The Abura-akago is a peculiar entity among Japanese yōkai, embodying the fusion of innocence and mischief through its dual nature as both a spectral infant and a wandering flame.

The creature originates from the folklore in the Ōmi Province—now part of modern Shiga Prefecture. According to the stories, this yōkai drifts through the night sky as an orb of fire, only to infiltrate homes and temples where it shapeshifts into a baby form to lap up precious lamp oil.

However, unlike more malevolent spirits, the Abura-akago poses no direct threat to human life. Instead, it disrupts daily routines by extinguishing lights and emptying lanterns, leaving residents in sudden darkness.

Summary

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Abura-akago (primary); alternate forms include abura-name akago (oil-licking baby) and hi no ko (child of fire). |

| Translation | Oil baby—directly from “abura” (oil) and “akago” (baby). |

| Title | Oil-licking infant spirit. |

| Type | Obake (shapeshifting ghost); subclass of hi no tama (fireball spirits). |

| Origin | Spirit of a deceased oil thief, cursed to wander as a flame for stealing from sacred lamps, such as those at Jizō statues. |

| Gender | Ambiguous—depicted as an infant without specified sex. |

| Appearance | Orb of floating fire transforming into a small, bald baby with pale skin, often clad in traditional swaddling; features a long, protruding tongue for licking oil. |

| Powers/Abilities | Shapeshifting between fireball and infant forms; nocturnal flight; oil consumption that drains lanterns completely. |

| Weaknesses | No explicit vulnerabilities in lore, though its fixation on oil lamps can be used to lure or trap it; repelled by extinguishing lights or using modern alternatives. |

| Habitat | Human settlements in Ōmi Province (Shiga Prefecture), especially homes and temples with oil lanterns; nocturnal wanderer. |

| Diet/Prey | Lamp oil from andon lanterns and paper lamps; targets fish- or seed-based fuels. |

| Symbolic Item | Andon lantern—represents both sustenance and the site of mischief. |

| Symbolism | Consequences of greed and theft; the preciousness of resources; blending of innocence (baby form) with disruption (fire and oil theft). |

| Sources | Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki by Toriyama Sekien; Shokoku Rijin Dan; Honchō Koji Innen Shū; Tōhoku Kaidan no Tabi by Yamada Norio. |

Who or What is Abura-akago?

Abura-akago is a yōkai classified as an infant spirit or ghostly apparition that bridges the realms of fire and human vulnerability. At its core, this entity manifests as a harmless yet intrusive presence, drawn inevitably to the glow of oil lamps in the dead of night.

Unlike vengeful ghosts or monstrous demons, the Abura-akago embodies a subtler form of supernatural mischief: it enters homes not to harm but to indulge in a simple, insatiable craving for oil—the lifeblood of illumination in Edo-period Japan.

According to experts in yōkai lore, the Abura-akago is a product of karmic retribution, where the soul of a greedy merchant, denied peaceful rest, reincarnates as this flickering being. Its dual form—a drifting fireball that morphs into a cherubic baby—evokes both amazement and unease.

“Abura-akago” Meaning

The name “Abura-akago” derives directly from classical Japanese, encapsulating the essence of this yōkai in two evocative syllables: abura and akago.

The term abura (油) refers to oil, particularly the viscous, fish-derived fuel that powered lanterns and hearths in pre-modern Japan—a substance so vital and laborious to produce that its waste or theft warranted supernatural reprisal.

Paired with akago (赤子), meaning “newborn baby” or “infant,” the full name paints a vivid image of innocence corrupted by gluttony. This linguistic fusion highlights the yōkai’s paradoxical nature: the purity of a child tainted by an adult vice.

Etymologically, abura traces its roots to ancient Sino-Japanese borrowings, which entered the lexicon during the Nara period (710–794 CE) as Japan adopted Chinese characters for trade and technological purposes.

Oil, imported or extracted locally from sesame seeds, whales, or fish livers, symbolized prosperity yet peril. Its scarcity fueled moral tales warning against excess. Akago, meanwhile, evokes vulnerability—used in classical texts like the Kojiki to denote helpless offspring—yet here it twists into something uncanny.

Historical evolutions of the name are evident in Edo-period (1603–1868) literature, where variations like abura-name akago (“oil-licking baby”) underscore the act of consumption, as seen in many regional kaidan (ghost stories). In Tōhoku Kaidan no Tabi, for instance, the term changes to highlight the slurping sound, adding auditory dread.

Toriyama Sekien’s 1779 Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki standardized Abura-akago, pulling from earlier fire-spirit motifs in Shokoku Rijin Dan (1740s), where unnamed “oil-stealing fires” (abura-nusumi no hi) prowled.

In the post-Meiji era (1868–1912), as electricity supplanted oil, the name persisted in urban legends, evolving to critique modern wastefulness.

Dialectal shifts in Ōmi Province rendered it abura-bō (oil priest) in some temple tales, blending infant imagery with clerical greed.

How to Pronounce “Abura-akago” in English

In English, Abura-akago is pronounced as “ah-boo-rah ah-kah-goh.” The first syllable, “ah-boo-rah,” rolls softly with a short “ah” like in “father,” followed by a breathy “boo” and a quick “rah.”

The second part, “ah-kah-goh,” mirrors this rhythm: “ah” is again open and relaxed, “kah” is crisp, and “goh” features a gentle guttural “g” that fades into “oh,” as in “go.”

Stress falls lightly on the first syllable of each word—A-bura A-kago—mimicking Japanese’s even pitch. Practice by breaking it down: say “ah-boo-rah” slowly, then add “ah-kah-goh,” ensuring a fluid connection without hard consonants.

What Does Abura-akago Look Like?

Depictions of the Abura-akago vary subtly across sources, yet combine in a form that masterfully blends the innocuous with the infernal.

In its primary manifestation, this spirit appears as a luminous orb of fire—a hi no tama no larger than a fist—pulsing with an eerie, bluish-white glow that mimics distant lantern light against the night sky. This fireball drifts silently and erratically (like embers caught in a breeze), casting fleeting shadows that might fool a weary traveler into mistaking it for a lost soul or a wandering spark.

Toriyama Sekien’s illustration in Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki captures this phase vividly: a compact flame, unadorned and hypnotic, symbolizing the untethered wrath of a thieved life.

Upon nearing a target—be it a humble farmhouse or sacred temple—the orb experiences a stunning metamorphosis, elongating and solidifying into the shape of a human infant.

This baby form dominates most folklore renderings: a diminutive figure, perhaps the size of a one-year-old, with smooth, pallid skin that gleams unnaturally under moonlight, devoid of the ruddy flush of living flesh.

Bald or sparsely tufted with fine, ethereal hair, it lacks distinct facial features beyond wide, unblinking eyes that reflect flickering flames—eyes that convey neither malice nor joy, but an insatiable hunger.

Covered in tattered swaddling reminiscent of Edo-period infant wrappings, the Abura-akago often perches precariously on lantern edges, its most striking trait being a long, twisting tongue that uncoils like a tendril to lap at oil reservoirs. This appendage, slick and prehensile, extends far beyond human proportions, slurping noisily and leaving greasy trails that sizzle faintly.

In Shiga Prefecture tales, the infant might don miniature robes echoing a merchant’s garb, nodding to its origins as a thief. At the same time, Akita folklore in Tōhoku Kaidan no Tabi portrays it suckling directly from wicks, cheeks bulging comically yet grotesquely.

Ukiyo-e prints exaggerate the contrast: the fireball’s stark simplicity against the baby’s chubby limbs, emphasizing transformation as a hallmark of yōkai.

You may also enjoy:

Who Were the Hinn, the First Spirits of Creation?

November 12, 2025

Setcheh: Egypt’s Soul-Stealing Ancient Demon

November 11, 2025

Arati: The Beautiful Demon of Aversion in Buddhist Mythology

October 15, 2025

Who Is Arioch, the Demon of War and Vengeance?

January 21, 2026

Alû: The Mesopotamian Demon of Malevolence and Pestilence

November 10, 2025

What Is the Abumi-guchi Yōkai and Why Does It Wait Forever?

October 22, 2025

Habitat

Abura-akago favors the intimate confines of human settlements, particularly those in the historic Ōmi Province (present-day Shiga Prefecture), where rolling hills and lake-dotted landscapes once amplified the isolation of rural homes.

These spirits shun wild forests or desolate mountains, drawn instead to the warm flicker of andon lanterns illuminating tatami-floored rooms, kitchens, and temple alcoves.

Why such domestic realms? Folklore posits that oil—their sole sustenance—abounded in these spaces, where families relied on sesame or fish-derived fuels for evening rituals, storytelling, or warding off the dark. Temples—especially those honoring Jizō (the protector of travelers and children)—hold an ironic appeal: sacred lamps, meant to guide souls, become feasts for the cursed thief reborn.

Nocturnal by nature, Abura-akago typically appears post-sunset, when shadows lengthen and winds carry the scent of burning wicks. They haunt corridors of prosperity—wealthier households with multiple lanterns risk multiple visits—yet spare the poorest, whose single, sputtering light might not entice.

According to the lore, its arrival is preceded by certain omens—a sudden chill despite the fire, or lanterns dimming inexplicably, as if oil evaporates on its own. In Ōtsu town’s Hacchō district, locals once whispered of “errant fires” (abura-bō) circling crossroads before darting indoors, a sign to bolt shutters or douse flames preemptively.

Origins and History

The Abura-akago was first mentioned in writing during the Edo period (1603–1868), a time when urbanizing society combined Shinto animism, Buddhist karma, and emerging literacy to give rise to myriad spirits.

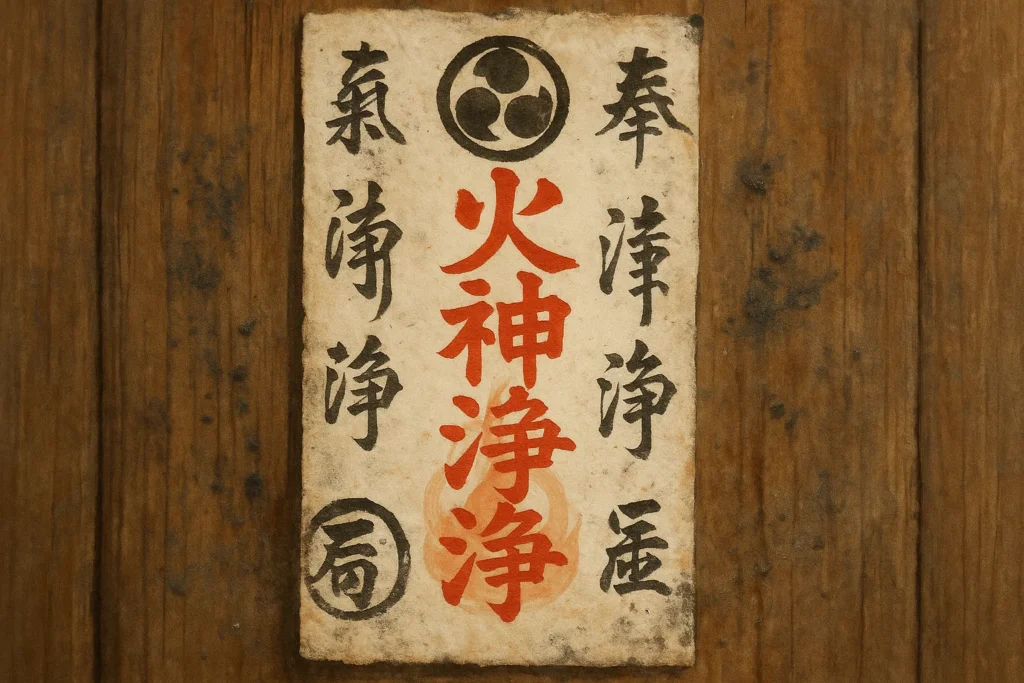

Its earliest documented appearance is in Toriyama Sekien’s 1779 illustrated encyclopedia, Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki (“Supplement to the Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Demons”), where the artist—renowned for cataloging supernatural beings—depicts the yōkai as a lamp-licking infant, complete with explanatory verse.

This work, part of Sekien’s four-volume series on hyakki yagyō (night parades of demons), popularized the Abura-akago, transforming a regional whisper into national fascination. Yet, Sekien did not invent it wholesale; he wove threads from older folk beliefs, particularly anxieties over oil scarcity amid feudal Japan’s resource strains.

Historically, oil’s centrality amplified such tales. From the Heian period (794–1185), whale and fish oils lit the noble courts, but by the Muromachi period (1336–1573), rural extraction from tea seeds or sesame had become laborious drudgery—yielding mere droplets per harvest.

Theft, especially from sacred sites like Jizō shrines (guardians against misfortune), often invited divine ire, giving rise to legends of souls trapped as flames.

The Abura-akago’s backstory mirrors this: a greedy merchant from Shiga’s villages, habitually siphoning temple lamps for profit, dies unrepentant. Denied nirvana, his essence ignites as a hitodama (soul fire), cursed to eternally seek what he stole.

This karmic loop, influenced by Buddhist concepts of gaki (hungry ghosts), evolved amid religious syncretism; Shinto’s nature spirits infused the fireball motif, while Zen tales of impermanence added poignant rebirth as a babe—helpless, yet driven by undying vice.

Over centuries, the yōkai adapted to societal shifts. During the Genroku era (1688–1704), booming woodblock printing spread Sekien’s image, embedding Abura-akago in kaidan (ghost stories) recited at gatherings.

Wars like the Ōnin (1467–1477) ravaged supply lines, heightening the value of oil and fueling similar spirits—ubagabi (old hag fires) or abura sumashi (oil-pressers)—as communal warnings against hoarding.

Natural disasters (such as the 1707 Hōei earthquake) spawned fire-phobia variants, with survivors attributing unexplained blazes to thieving ghosts.

Meiji modernization (1868 onward) marginalized oil lamps, yet preserved the legend in literature; Yanagita Kunio’s 1910 folklore studies reframed it as cultural memory, linking cat-licking shadows to misperceived hauntings.

Sources

The Abura-akago does not feature in ancient texts like the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki, which focus on divine kami rather than later folk spirits. Its appearances cluster in Edo-period compilations, where Toriyama Sekien and others elaborated on pre-existing fire legends.

| Source | Quote |

|---|---|

| Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki (Toriyama Sekien, 1779) | 近江国(あふみのくに)大津の八町に玉のごとくの火飛行(ひぎやう)する事あり。土人云、むかし志賀の里に油をうるものあり、夜毎に大津辻の地蔵の油をぬすみけるが、その者死て魂魄炎となりて今に迷ひの火となれるとぞ。しからば油をなむる赤子は此ものの再生せしにや。 In Hacchō, Ōtsu in Ōmi (“Afumi”) Province, there exists a flying ball-like fire. The natives say that long ago in the village of Shiga there was an oil merchant, and every night he stole the oil from the Jizō of the Ōtsu crossroads, but when this person died his soul became a flame and even now they grow accustomed to this errant fire. If it is so, then the baby who licks the oil is this person’s rebirth. |

| Shokoku Rijin Dan (Kikuka Chōryō, 1740s) | 油盗みの火(abura-nusumi no hi)—志賀の里の油売りが、地蔵の灯油を盗み、死後迷火となる。 The oil-stealing fire—in the village of Shiga, an oil seller stole from the Jizō’s lamp oil, and after death became a wandering flame. |

| Honchō Koji Innen Shū (early 18th century) | 大津の油盜人、死して火の玉となり、夜な夜な灯を舐む。 The oil thief of Ōtsu, dying to become a fireball, licks lamps night after night. |

| Tōhoku Kaidan no Tabi (Yamada Norio, 1974) | 油舐め赤子(abura-name akago)—秋田の女、赤子を負ひ宿に泊る。赤子、提灯の油を尽く吸ひ干す。 Oil-licking baby—a woman carrying a baby stays at a village head’s house in Akita; the baby sucks dry all the lantern’s oil. |

| Honchō Nijū Fukō (Ihara Saikaku, 1698) | 赤子油を啜る不孝—灯火の油を赤子が飲み干し、家を暗闇に陥る。 The unfilial act of the baby drinking oil—the infant drains the lamp, plunging the house into darkness. |

Famous Abura-akago Legends and Stories

The Oil Merchant’s Eternal Flame

In the quiet streets of Ōtsu, in the misty region of Ōmi Province, there lived a crafty oil seller. This man specialized in oils made from fish and pressed tea seeds.

By day, he charmed people with sweet talk to sell his products, but by night, he turned to theft. As the villagers slept, he snuck to a small shrine where stone statues of Jizō stood, watching over travelers and those in need.

With quick movements, he stole the sacred oil meant to keep the statues lit and sold it at the market. “Why should the gods keep what helps the living?” he would say, pocketing his stolen treasures.

As time passed, he became wealthy, but hidden guilt consumed him.

When he finally died suddenly from a fever in his home, his spirit lingered instead of moving on. It transformed into a wandering fireball, a hitodama, drifting through the night with a desire for revenge. People first noticed it on dark nights, a glowing orb flitting between homes in Hacchō, drawn to windows like a moth to a flame.

One stormy evening, while a seamstress worked on a kimono near her lamp, the glowing orb slipped inside. It expanded into the shape of a small child, with a bald head and wrapped in ghostly rags.

The child climbed onto the lamp, its long tongue reaching out greedily to drink the oil. “Yummy… more,” it said, sounding like rustling leaves, until the lamp ran dry and the wick turned black.

The terrified seamstress ran outside into the rain, and when dawn broke, only greasy marks remained where the orb had been. News spread quickly: the oil seller’s ghost, now a hungry little spirit, haunted his old neighborhood, forever searching for the oil he craved.

Villagers began to snuff out their lights at night and prayed to Jizō for mercy. Yet the ghostly flame continued its haunting, bringing a clear message: stealing from the sacred brings not wealth, but an unending desire.

You may also enjoy:

Setcheh: Egypt’s Soul-Stealing Ancient Demon

November 11, 2025

What Is a Rakshasa? Meaning, Origins, and Dark Powers

January 23, 2026

Who Was Mahishasura, the Buffalo Demon Slain by Goddess Durga?

October 3, 2025

Ifrit: Demon of Fire Who Serves Iblis in Islamic Tradition

September 30, 2025

Amaymon: The Infernal King Who Commands Death and Decay

November 17, 2025

Demon Alastor: The Grand Executioner of Hell

November 17, 2025

The Traveler’s Drained Vigil

In the northern region of Akita, away from the serene lakes of Ōmi, a tired traveler sought refuge in the home of a village elder, known as the shōya. Dressed in worn robes from his pilgrimage, he carried stories of far-off shrines and asked for a place to rest from the fierce winds.

The kind shōya welcomed him warmly, leading him to a small guest corner where a single lamp cast a soft, golden light on the floor. “Rest well, wanderer,” the shōya said gently, closing the sliding doors behind him. “Our lamp will guide you through the night.”

As midnight approached, a strange silence fell over the house. The traveler stirred, his eyes adjusting to the dim light. He noticed the shōya’s wife softly singing lullabies to their real, sleeping baby nearby.

Suddenly, a strange, glowing creature appeared from above—a mischievous spirit known as an abura-akago, attracted by the lamp’s light. It floated like a tiny drunk firefly before transforming into a plump baby with hungry eyes.

The creature crawled quickly, gripping the lamp’s stand with its small hands. Its long tongue stretched out, dipping into the oil reservoir, sucking greedily.

With each drink, the flame flickered and dimmed as the oil disappeared. After satisfying its hunger, the imp burped, a bubble of oil bursting on its lips, before it turned back into a glow and vanished through the ceiling.

When dawn broke, chaos filled the room. The lamp was empty, oil stains marked the floor, and the real baby cried in confusion. The traveler, knowledgeable about such strange happenings, recognized the spirit as an oil-sucking imp born from the misty northern regions where spirits gather.

The shōya listened intently, recalling tales he had heard: last harvest, this creature had drained the lamps in the temple, forcing monks to chant without light.

To prevent a repeat of this disturbance, they burned cedar wood at their doorways. They promised to offer untouched oil to the roadside statue of Jizō, a protector of travelers.

The Midnight Gathering of Flames

Another fascinating story comes from Ihara Saikaku’s collection, the ukiyo-zoshi, where extravagance meets the supernatural.

Set against the backdrop of bustling Kyoto, a flashy merchant, who made his fortune in silk trading, decided to throw an extravagant party in his beautifully lit pavilion. As guests indulged in drinks that flowed like water and geishas entertained with their melodic shamisen, something strange happened one hot summer night.

From the horizon, eight glowing orbs appeared, drawn by the warmth of the dozens of lanterns flickering in the night. They danced through open doors, transforming into tiny, wiggling figures that resembled cheerful, bald babies, giggling with voices that tinkled like wind chimes.

One of the smallest climbed atop a lamp and called out to its kin, “Come on, everyone! Let’s feast!” It began splashing oil around, which sizzled as it hit the ground.

The other little spirits joined in, forming a circle around the flames of the lamps and slurping up the oil. As the oil levels dropped, the flames started to dance wildly, casting strange, moving shadows of the little creatures on the walls.

The guests were frozen in a mix of panic and laughter. One noblewoman even screamed, calling them “disobedient little brats!”. At the same time, a samurai drew his sword, but he only ended up slicing through empty air. The mischievous spirits continued to party, gathering empty containers as trophies before merging into one bright fire and shooting back into the sky.

When morning came, the pavilion smelled strongly of fish oil, the lamps were empty, and the guests awoke with headaches, along with wild stories from the night. Saikaku referred to this as “the twenty unfilial acts,” suggesting that the spirits’ overindulgence echoed human folly.

Abura-akago Powers and Abilities

The Abura-akago wields a modest arsenal of supernatural talents, centered on evasion and sustenance rather than domination, rendering it less formidable than hulking oni or illusion-weaving kitsune.

Its strength lies in subtlety: a low-tier yōkai in the hierarchy, capable of nuisance but not conquest, it disrupts rather than destroys, akin to a pesky zashiki-warashi house spirit but with fiery caprice.

Compared to peers, it ranks below mid-level threats like rokurokubi (neck-stretchers that spy and strangle), yet above harmless bakechochin (lantern ghosts).

Its oil affinity grants persistence in lit domains, but daylight banishes it utterly, underscoring its vulnerability to progress.

Abura-akago’s powers and abilities include:

- Shapeshifting: Seamlessly alternates between a compact fireball (hi no tama) for flight and an infant guise for close-quarters access; this allows infiltration through slits too narrow for solid forms.

- Nocturnal Levitation: Drifts silently at low altitudes, navigating winds without fatigue; enables house-to-house prowls covering miles nightly.

- Oil Consumption: Drains lantern reservoirs completely via elongated tongue, extinguishing lights instantaneously; implied to absorb fuel for sustenance, growing brighter post-feast.

- Spectral Intangibility: Passes through barriers like paper screens or thatch as vaporous flame; resists mundane weapons, phasing like smoke.

- Group Manifestation: In rare tales, summons kin for collective raids, amplifying drain on multiple lamps; fosters eerie, harmonious gatherings.

- Illusory Cuteness: The infant form evokes misplaced trust, delaying the human response; eyes and coos disarm, buying time for theft.

How to Defend Against Abura-akago

When it comes to dealing with the mysterious Abura-akago, there are practical ways to keep it at bay without resorting to heavy exorcisms.

The best strategy is to prevent it from being attracted to your home in the first place. As night falls, make sure to turn off all paper lanterns and andon lights, leaving your space intentionally dark. This helps deprive the Abura-akago of its favorite lure, which is light.

For additional protection, consider using cedar branches at your doorways. When burned, these branches release a strong-smelling smoke that repels the Abura-akago, making the air unwelcoming for it.

You can also create a salt barrier around your hearth or bed. When sprinkled, the salt protects the space. It has a cleansing effect, causing the spirit to dissipate into a harmless vapor.

If you’re feeling adventurous, you might try enticing the spirit away. Set up a bait lamp outside filled with vinegar or salty brine, which smells like spoiled oil. The Abura-akago might be drawn to it, eat too much, and then leave weakened.

Making offerings to Jizō, such as rice balls or empty oil containers, can also help calm the spirit. Stories from Shiga suggest that these offerings have successfully stopped hauntings.

It’s essential to acknowledge that the Abura-akago has certain limitations. For one, it’s unable to withstand the daylight, which completely extinguishes its flame.

Unlike other spirits, it also can’t focus if there’s loud noise, like ringing bells or shouting, which can disrupt its concentration.

Abura-akago vs Other Yōkai

| Name | Category of Yōkai | Origin | Threat Level | Escape Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kasa-obake | Tsukumogami | Abandoned umbrella gaining sentience after 100 years. | Low | Easy—amuse it with play; hops away if entertained. |

| Zashiki-warashi | Obake | Spirit of deceased child haunting prosperous homes. | Low (benign) | Easy—leaving angers it, but offerings retain luck. |

| Abura Sumashi | Hi no Tama | Ghost of oil thief fleeing to woods post-crime. | Low | Moderate—hides in passes; fire-starting tools repel. |

| Ubagabi | Hi no Tama | Old woman’s vengeful fire from unattended hearth. | Medium | Moderate—flares wildly; water douses, but spreads fast. |

| Rokurokubi | Obake | Cursed woman’s neck elongates at night for mischief. | Medium | Hard—spies undetected; severing hair breaks curse. |

| Kappa | Obake | River child-spirit warped by drowning or mutation. | High | Hard—water weakness, but cunning lures demand wit. |

| Kitsune | Yōkai | Fox spirit ascending through age and illusion mastery. | Variable | Hard—shapeshifts convincingly; truth mirrors expose. |

| Bakeneko | Obake | Cat gaining powers after tail-tip injury or age. | Medium-High | Moderate—fire fears it; but revenge escalates. |

| Yuki-onna | Yūrei | Snow woman’s ghost from frozen deaths in mountains. | High | Very Hard—icy breath freezes; vows bind eternally. |

| Tengu | Oni | Bird-demon from arrogant monks or mountain ascetics. | High | Very Hard—flight and winds thwart; humility appeases. |

| Kawa-akago | Obake | Crying river baby luring victims to watery graves. | Medium | Moderate—ignores cries; but echoes persist. |

| Chochi Odori | Tsukumogami | Dancing dust bunnies from hearth ashes in neglect. | Low | Easy—sweeping cleanses; joins dances harmlessly. |

| Hi no Tama | Yūrei | Generic soul fire from unburied corpses or regrets. | Low-Medium | Easy—prayers guide it; lingers if ignored. |

Symbolism

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Element | Fire—embodies the flickering, consuming nature of flames tied to oil theft and nocturnal wanderings. |

| Animal | Cat—shadows of felines licking lamps may have inspired sightings, linking to stealthy predation. |

| Cardinal Direction | East—aligned with Ōmi Province’s location and dawn’s purifying light, per Onmyōdō cosmology. |

| Color | Yellow-Orange—evokes warm lantern glow and greedy consumption, contrasting cool night blues. |

| Plant | Sesame—source of pressed oil for lamps; offerings deter through overabundance. |

| Season | Summer—nights alive with fireflies and festivals, amplifying oil’s festive yet wasteful use. |

| Symbolic Item | Andon Lantern—core to its mischief, representing fragile human light against supernatural dark. |

In Japanese culture, the Abura-akago symbolizes the perils of greed and the sanctity of communal resources, serving as a moral fable amid the feudal scarcity of resources.

As the ghost of a petty thief reborn in infantile guise, it personifies how unchecked greed disrupts harmony—stealing not just oil, but the security of light that binds families.

This duality—invisible flame yielding to vulnerable babe—mirrors societal taboos around exploiting the sacred, like Jizō’s lamps meant for lost souls; theft invites karmic exile, echoing Buddhist warnings against attachment. During Obon festivals, where ancestral fires roam, it embodies unresolved regrets, urging offerings to pacify wandering spirits.

You may also enjoy:

Amenadiel: Origins, Hierarchy, and Demonic Attributes

January 5, 2026

Allocer: Great Duke of Hell and the 52nd Spirit of the Ars Goetia

November 17, 2025

Aamon: The Infernal Marquis of Lust, Feuds, and False Prophecies

September 29, 2025

Who Is Ahriman, and Why Is He Pure Evil Incarnate?

January 8, 2026

Rāga: The Seductive Demon of Passion and Desire in Buddhist Lore

October 16, 2025

Erinyes: The Chthonic Goddesses Who Enforced Blood-Guilt

November 20, 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Abura-akago?

Abura-akago is a Japanese yōkai depicted as a floating fireball that shapeshifts into an infant to steal lamp oil from homes and temples, originating from Edo-period folklore in Ōmi Province. It embodies the cursed soul of a greedy oil thief, blending mischief with karmic retribution without posing lethal threats. In contemporary media, such as Yo-kai Watch, it’s reimagined as a quirky collectible.

What does the name Abura-akago mean?

The name Abura-akago literally translates to “oil baby,” from “abura” (oil) and “akago” (infant), capturing its essence as a child-like spirit fixated on consuming lantern fuel.

Is Abura-akago dangerous or evil?

Abura-akago is mischievous rather than evil or dangerous, merely extinguishing lights through oil theft without harming people, unlike vengeful yūrei. Its curse-driven actions symbolize the fallout of petty greed, offering a lighter contrast to the malevolent yōkai in lore.

What do Abura-akago stories teach?

Abura-akago legends teach lessons on the consequences of theft and the sanctity of shared resources, using its baby guise to illustrate how small sins echo eternally.