The Abumi-guchi is a small yōkai in Japanese folklore. Unlike many other similar demonic entities that are often mischievous or vengeful, the Abumi-guchi has a more touching story.

This creature is a type of spirit known as a tsukumogami, which comes to life when an object is forgotten or neglected. In the case of Abumi-guchi, the tiny creature came to life from an iron stirrup used by a samurai. When the samurai tragically died in battle, his horse was also left behind on the battlefield.

Instead of seeking revenge or causing trouble, the Abumi-guchi remains in the same spot, resembling a small, furry guardian. It patiently waits for its master to come back, even though it knows that will never happen.

Key Takeaways

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Names | Abumi-guchi; alternate spellings include Abumi-kuchi or Abumiguchi |

| Translation | Stirrup mouth |

| Title | None; occasionally called the “loyal battlefield sentinel” |

| Type | Tsukumogami (tool spirit yōkai) |

| Origin | Forms from a discarded stirrup of a fallen samurai after 100 years of neglect or sudden abandonment in battle |

| Gender | Ambiguous; no specified gender in legends |

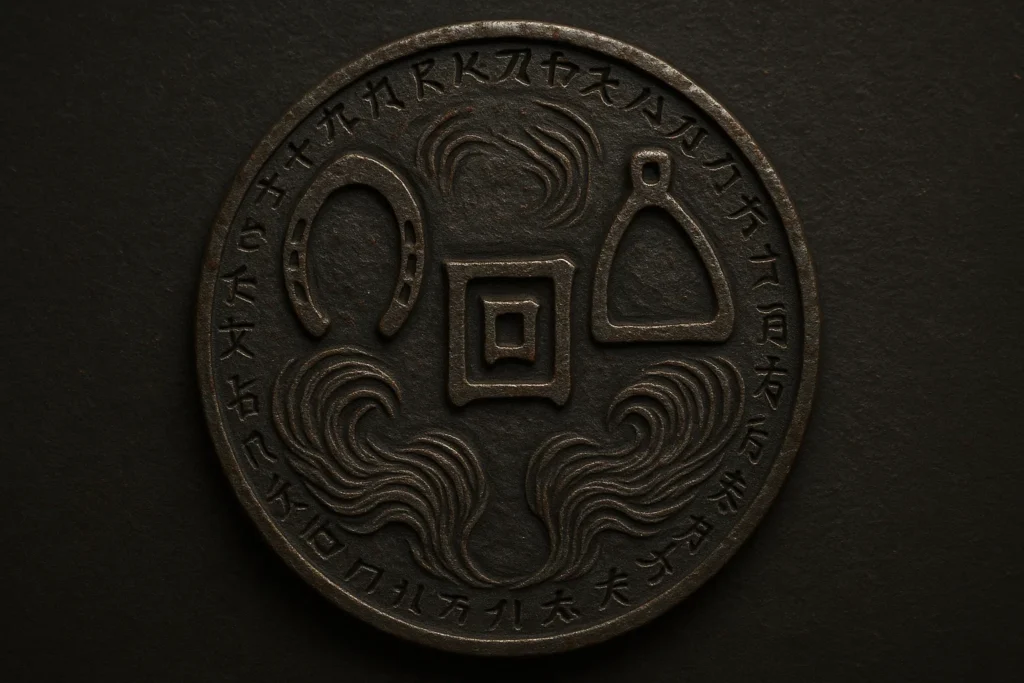

| Appearance | Small, furry creature resembling a woolly beast with a metal stirrup for a mouth and leather straps as arms or limbs |

| Powers/Abilities | Sentience and mobility after transformation; eternal vigilance without need for sustenance |

| Weaknesses | Harmless by nature; can be appeased by offerings or rituals honoring the dead; vulnerable to destruction of its physical form |

| Habitat | Battlefields, abandoned fields, or rural meadows where wars once raged |

| Diet/Prey | None; does not consume or target anything |

| Symbolic Item | Abumi (stirrup) |

| Symbolism | Loyalty in loss; the futility of waiting; the human cost of warfare |

| Sources | Gazu Hyakki Tsurezure Bukuro by Toriyama Sekien; later compilations like Hyakkai Zukan |

Who or What is Abumi-guchi?

The Abumi-guchi is a type of tsukumogami (a spirit that comes to life from everyday objects after they’ve served their purpose for a long time) from Japanese folklore known as a tsukumogami.

This particular spirit comes from the abumi (a stirrup used by mounted warriors in the past). After many decades—perhaps even centuries—the metal rusts, the leather ages, and something magical happens: the Abumi-guchi begins to stir to life.

Unlike some other spirits that might be scary or seek revenge, the Abumi-guchi is gentle and holds deep feelings of loyalty. It shuffles around on short limbs made from worn-out straps, and its wide-open mouth seems to call out for a rider who is no longer there.

The essence of this yōkai is in its quiet nature. It doesn’t cause trouble or seek vengeance. Instead, it acts as a keeper of memories, standing still like a living tribute to those who have been lost.

“Abumi-guchi” Meaning

The name “Abumi-guchi” is rooted in both its physical appearance and its role in Japanese folklore, combining literal and symbolic meanings.

To break it down, “abumi” refers to a stirrup. Stirrups are the U-shaped metal pieces attached to a saddle that help riders to mount and keep their balance while riding horses—especially during battles since the Heian period (794–1185 CE). The concept of the stirrup comes from ancient Chinese influences on Japanese metalwork, evolving from words that described horse gear.

The second part, “guchi,” means “mouth,” which resembles the open shape of the stirrup. This gives a human-like quality to the stirrup, making it more expressive and poetic.

So, “Abumi-guchi” can be understood as “stirrup mouth,” suggesting a creature with a metallic mouth that seems to be making sounds—like a sigh, a call, or even a lament.

The way this name is formed ties into a larger tradition in Japanese folklore, where ordinary items are combined with descriptions related to human behavior or features to create names that feel more relatable. Sometimes, you might see it written as “Abumi-kuchi,” with a different pronunciation for “mouth,” which emphasizes that aspect.

Toriyama Sekien and other artists from the Edo period often used variations of the name as a stylistic device. Historically, the meaning of Abumi-guchi has evolved in tandem with Japanese culture.

During the Kamakura period, when the samurai class was at its height, the use of stirrups became a symbol of martial skill, so losing them in battle was considered a bad omen. By the Genroku period (1688–1704), the name had found its place in art, shifting from battlefield slang to a recognized part of folklore.

Unlike many other mythical creatures that have multiple regional names, Abumi-guchi has remained fairly consistent, even though in some rural areas, it might be referred to as “Abumiguchi.”

How to Pronounce “Abumi-guchi” in English

In English, Abumi-guchi sounds like “ah-boo-mee-goo-chee.” Stress falls lightly on the second syllable (boo), with a soft roll on the “r”-like flap in guchi—think “goo-chee,” akin to “gooey” but clipped.

The “a” in abumi is a neutral schwa (uh), while vowels stay pure: no harsh “uh” diphthongs. Practice by breaking it: Ah-boo (as in “boot” without “t”); mee (like “me”); goo (rhyming with “boo”); chee (as in “cheese” sans “s”).

What Does Abumi-guchi Look Like?

The Abumi-guchi’s shape pays tribute to its origin as an old, forgotten stirrup used in saddles. Its wide U-shaped mouth looks like it’s caught in a moment of whinnying or begging for attention, and it dominates its face.

The tiny yōkai is covered in a messy fur, thick and untamed, with earthy colors like browns and grays. It resembles the tangled hair of a stray animal or the underbrush of a forest. The fur puffs out all around its body, giving the Abumi-guchi a cute, squat shape reminiscent of a teddy bear, standing only about the height of a child’s knee.

The creature has two makeshift arms made from leather straps that used to hold the stirrup in place. These arms dangle loosely, appearing worn and frayed, as if they’ve been neglected for years. As a result, the Abumi-guchi shuffles rather than walks, moving with a deliberate waddle across the grass.

Its small, beady eyes peek out from under its furry brows, sometimes glowing faintly in dark illustrations. In some artworks, these eyes are absent, suggesting that the creature navigates the world more by instinct than by sight.

The body doesn’t have visible legs, which gives the impression that it either drags itself along the ground or floats just above it.

While there are slight variations in how the Abumi-guchi is depicted, the core features remain the same.

Habitat

The Abumi-guchi is a creature that haunts places marked by conflict (old battlefields and grassy fields where the memories of fighting still linger). These locations—such as the historic plains near Sekigahara or forgotten sites around Kyoto—are perfect for the Abumi-guchi to appear.

Why does it prefer these areas? Folklore suggests that they are infused with the lingering spirits of those who have died there. For example, an abandoned samurai’s stirrup, left behind in chaos, absorbs the emotions and stories of fallen warriors, transforming into something otherworldly over time.

Unlike other mythical beings—like the river-dwelling kappa or the mountain-dwelling tengu—the Abumi-guchi avoids forests and villages. It is tied to the ground it roams, which keeps it from wandering far away. Instead, it moves silently through tall grass under the stars, careful to stay out of the light of dawn.

People rarely encounter the Abumi-guchi, but those who do—especially hunters, poets, or lost travelers—often cross these haunted areas at dusk.

Local legends claim that certain items—such as unattended grave lanterns or unburied relics from battle—can accidentally summon it. However, it doesn’t come aggressively; instead, it appears as a ghostly presence, brushing gently against your ankles.

Origins and History

The Abumi-guchi’s story likely began during the late Heian period (around 1100 CE) amidst the turbulent battles of the Genpei War between two powerful clans. During these conflicts, samurai relied heavily on horses, and stirrups—essential for archers to shoot accurately—were scattered across the battlefields.

However, the Abumi-guchi really took shape as a recognized spirit during the Edo period (1603–1868), a time when Japan enjoyed peace and scholars began to explore and document the supernatural.

In earlier tales, objects (like old tools) were seen as spirits—or kami—restless and searching for purpose. After the unification of Japan following the Sengoku period, artists and storytellers began to categorize these stories into a group known as tsukumogami—spirits of tools that came to life, reflecting a blend of beliefs from both Shinto and Buddhism.

The Abumi-guchi emerged from this mix, representing a longing for the lost honor of the samurai.

Different historical events also shaped its story. The Mongol invasions in the 13th century led to tales of animated weapons and gear, while natural disasters (like typhoons) stirred fears that the souls of fallen warriors might cling to their lost possessions.

Over the years, the Abumi-guchi transformed from a scary omen into a more sympathetic figure. With the modernization of Japan during the Meiji period (1868 -1912), this spirit faded from the spotlight due to Western influences. However, it found new life in rural ghost stories, subtly critiquing the impact of warfare.

You may also enjoy:

Who Is Ambolin, the Demon of Nighttime Dread

December 1, 2025

Tarakasura: The Dark Demon Who Ruled Hell on Earth

December 4, 2025

Erinyes: The Chthonic Goddesses Who Enforced Blood-Guilt

November 20, 2025

What Is the Abumi-guchi Yōkai and Why Does It Wait Forever?

October 22, 2025

Who Are the Yaksha, and Why Did Buddhists Fear Their Wrath?

October 20, 2025

Edimmu: The Mesopotamian Wind Demon That Steals Life

November 6, 2025

Sources

The Abumi-guchi is first attested in Edo-period illustrated encyclopedias, where it appears as a minor yet evocative entry among the nocturnal parades of spirits.

Unlike ancient chronicles—like the Kojiki (712 CE)—which favor divine kami over tool-born anomalies, it thrives in artistic compilations that democratize folklore for urban audiences.

| Source | Quote |

|---|---|

| Gazu Hyakki Tsurezure Bukuro (Toriyama Sekien, 1776) | Original (Japanese): 鐙口 古き鐙の口の如し 戦場に捨てられし鐙かな Translation: “Stirrup mouth—like the maw of an ancient stirrup. Ah, the stirrup discarded on the battlefield.” (Accompanying poem; illustration depicts the furry form awaiting its master.) |

| Hyakkai Zukan (Sawaki Suushi, ca. 1737; influences Sekien) | No direct quote; referenced in derivative sketches as “abumi no tama” (stirrup spirit), with visual motifs of leather-limbed furballs in war-torn fields. |

| Obakemono Project Compilation (Modern folklore archive, drawing from Edo kaidan) | “The abumi-guchi shuffles eternally, its iron jaws agape for a rider slain in forgotten fray—loyalty’s quiet curse.” (Paraphrased from oral variants) |

Famous Abumi-guchi Legends and Stories

Japanese folklore yields few extended tales for the Abumi-guchi, its lore favoring concise vignettes over epic sagas.

The Stirrup of Genpei’s Shadow

In the quiet aftermath of the last battle of the Genpei War at Yashima in 1185, Minamoto no Yoritomo’s troops defeated the Taira clan while the waves crashed around them. Among the chaos, a loyal warrior named Taro rode into battle.

Arrows flew through the air, and when one struck his horse, it reared up, throwing Taro into the sea. His horse’s saddle was lost, forgotten in the tumult of the retreat, and Taro drowned, his body swept away by the water as his comrades fled, their banners drooping in defeat.

Years went by, and the dunes where Taro fell became wild with grasses and bushes, hiding long-forgotten bones beneath the surface. One autumn evening, a hundred years later, a fisherman named Jiro cast his nets under a bright harvest moon.

Instead of catching fish, he snagged something unusual—a small, soft form that felt like fur but was as solid as metal. When he pulled it onto the shore, he discovered a strange creature that looked like it was covered in shaggy skin and stood no taller than a hare.

Leather straps hung from it like tired vines, and on its face was the shape of a stirrup, its mouth open as if asking a question, its eyes dark like polished stone.

Startled, Jiro murmured prayers for safety to Inari, the deity of rice and fertility. The creature didn’t act aggressively; instead, it moved around his feet as if looking for someone to ride it.

Though it didn’t speak words, the sound of the wind rustling through the grass seemed to echo its thoughts, “Master… mount?” Jiro, frightened yet fascinated, recalled the stories from the elders about spirit beings called tsukumogami, born from the remnants of war.

He offered food and sake at the top of the dune, calling upon Taro’s restless spirit. When dawn broke, the creature vanished into the mist, leaving only the marks of its stirrups in the sand, like tears shed for the past.

The Meadow Sentinel of Sekigahara

Centuries later, on the battlefield of Sekigahara in 1600, where Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated Ishida Mitsunari’s forces in a foggy dawn, a banner carrier named Kenji charged forward, holding his banner high.

However, his horse stumbled in the muddy ground and was hit by gunfire. Kenji fell off, losing his helmet in the underbrush. His stirrup broke and sank into the earth as his comrades fled, leaving behind a field littered with abandoned equipment.

Eighty years later, the meadow was now vibrant with flowers, like poppies, growing over mass graves. A wandering samurai named Hiroshi, a battle-hardened veteran of the Shimabara rebellion, set up camp among the remnants of the past, sharpening his sword by the firelight. As night fell and the fire dimmed, he heard a rustling sound nearby.

From the shadows, a strange creature appeared, short and sturdy, its jaws softly grinding against the pebbles. Its fur, tangled with fallen leaves, trembled in the cool night air.

Hiroshi instinctively drew his sword, his heart racing—had the spirits of Sekigahara come back? But instead of attacking, the creature paused, seemingly looking at him as if it understood his history.

It didn’t advance; instead, it settled down close to the fire, gazing towards the city of Edo, full of hope. Feeling a connection, Hiroshi shared his own painful memories—friends he lost at Osaka, the stirrups he couldn’t save during their escape.

He offered the creature some polished rice and spoke Kenji’s name, drawn from weathered grave markers. The creature leaned in closer, its metallic lips brushing against his boot—a sign of understanding rather than a threat.

By morning, it had vanished into the fog, leaving Hiroshi with an imprint of the stirrup on his palm, which warmed him like a home fire.

The Forgotten Relic of Yamato Takeru

This tale is connected to the legendary Prince Yamato Takeru, who is known for his heroic adventures around 200 CE.

During one fierce fight, his horse slipped on the rocky edge of a cliff and tumbled into a ravine. Though Takeru managed to escape, he accidentally left behind his prized stirrup, caught in the thorny bushes.

Over time, the ravine transformed into a lush, hidden glen. One day, a shrine maiden named Miko from Izumo ventured there to collect herbs during the summer solstice.

As dusk approached, she heard rustling in the underbrush and discovered a yōkai, a magical creature, with the abandoned stirrup shining with dew. This being didn’t come closer but mimicked her movements, as if repeating old promises.

Miko, knowledgeable in spiritual practices, understood that the stirrup had come to life due to being neglected by Takeru, showing how loyalty can endure through time.

Kneeling, she recited prayers and lit incense made from cypress wood. The Abumi-guchi trembled, shedding its fur like leaves in autumn, and filled Miko’s mind with visions of Takeru fighting bravely alongside his horse.

In gratitude for her respect and care, the yōkai gifted her a piece of its strap, which Miko used to create lucky charms at the shrine to protect people from wandering spirits. This once-forgotten glen became a popular place for pilgrims, who would leave polished metal pieces in honor of the stirrup’s long wait.

You may also enjoy:

Vritra: The Dragon Who Swallowed the Sky in Hindu Mythology

October 7, 2025

Aeshma: The Zoroastrian Demon of Wrath and Fury

January 13, 2026

Azhi Dahaka: The Three-Headed Dragon of Zoroastrian Mythology

January 14, 2026

Empusa: The Blood-Drinking Wraith of Greek Mythology

November 20, 2025

Who Was Hiranyaksha, the Golden-Eyed Asura?

October 7, 2025

Who Is the Demon Andras, The Great Marquis of Discord?

January 15, 2026

Abumi-guchi Powers and Abilities

While it may not seem as threatening as more famous yōkai (like the fierce oni, vengeful karakasa-kozō, or the tricky kitsune), the Abumi-guchi has its own kind of resilience. It remains unaffected by the passage of time, enduring long after more aggressive spirits have faded away.

Abumi-guchi’s most notable powers and abilities include:

- Eternal Vigilance: The Abumi-guchi stays in one spot forever, unaffected by the weather or time. It seems to maintain a link to its original owner, sensing their spirit even from afar.

- Sentient Mobility: It moves slowly, at a pace comparable to a person walking, using its leather limbs to shuffle along. Although it can’t fly or move quickly, it can navigate uneven ground without getting tired.

- Empathic Aura: When people encounter the Abumi-guchi, they often feel a wave of calm sadness that helps ease tensions. Many have reported feeling introspective or even brought to tears upon seeing it, which helps promote peaceful resolutions during conflicts.

- Form Manifestation: This spirit comes to life after being neglected for a long time—usually around 100 years. It draws energy from its surroundings to animate its fur and limbs. This transformation can be reversed through special purification rituals.

- Symbolic Resonance: The Abumi-guchi can absorb and reflect the energies of past battles, sometimes creating faint, ghostly images of those events. These illusions aren’t harmful; they serve as whispers from history, reminding us of what has come before.

How to Defend Against Abumi-guchi

Defending against the Abumi-guchi is quite simple because it is not harmful. Instead of fighting it, legends suggest that it’s better to appease this spirit, as it symbolizes devotion rather than destruction. The main “threat” it poses is causing feelings of regret or loneliness in those who encounter it, which can lead to sadness or distraction.

The Abumi-guchi has some weaknesses because it is tied to physical objects. It tends to fade away when people perform actions that represent closure (like traditional Shinto rituals for spirits that have not found peace).

Elders recommend carrying small paper talismans (ofuda), which have purifying symbols written on them. Keeping one in your sleeve and waving it can disrupt the spirit’s presence, causing it to retreat.

Another common defense involves creating barriers with salt. If you sprinkle salt in a circle around your campsite, the Abumi-guchi will steer clear, repelled by the purity of salt.

For those wanting to take a more proactive approach, leaving offerings can also be effective. Pouring a bit of sake into a small iron cup near places where the spirit may appear, while reciting the names of deceased ancestors, can be helpful.

Saying something like, “Rest, faithful one; your rider awaits in the next world,” shows respect. Moreover, placing rice balls wrapped in oak leaves at dawn symbolizes the nourishment it missed in life, enticing the spirit to rest.

Abumi-guchi vs Other Yōkai

| Name | Category of Yōkai | Origin | Threat Level | Escape Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karakasa-kozō | Tsukumogami | Abandoned umbrella gaining sentience after 100 years | Low (prankster) | Easy: Repel with shouts or closing the “mouth” |

| Biwa-bokuboku | Tsukumogami | Forgotten biwa lute animated by neglect | Low (noisy nuisance) | Moderate: Silence via stuffing or destruction |

| Chōchin-obake | Tsukumogami | Old lantern sprouting eyes and tongue | Low (startling) | Easy: Extinguish flame or cover with cloth |

| Bakezōri | Tsukumogami | Worn straw sandals come alive | Low (chaotic chase) | Easy: Trip with sticks or burn the soles |

| Kasa-obake | Tsukumogami | Parasol yōkai from discarded rain gear | Low (playful hops) | Easy: Fold it shut or stake to ground |

| Noppera-bō | Obake | Faceless ghost mimicking humans | Medium (psychological) | Moderate: Ignore or use mirrors to reveal true form |

| Nurikabe | Obake | Invisible wall spirit blocking paths | Low (annoying barrier) | Moderate: Crawl under or throw beans to dispel |

| Yūrei | Yūrei | Vengeful ghost of untimely death | High (haunting curse) | Difficult: Requires full exorcism rituals |

| Kappa | Obake | River imp from watery curse | High (drowning pull) | Moderate: Bow to spill water from head dish |

| Tengu | Oni-like | Mountain spirit from arrogant monks | Medium-High (wind tricks) | Difficult: Humility or sacred fans to counter |

| Kitsune | Yōkai | Fox spirit tied to Inari shrines | Variable (illusions) | Difficult: Iron faith or breaking foxfire |

| Oni | Oni | Demonic ogre from sinful souls | Very High (brute force) | Very Difficult: Clubs or sealed gates needed |

| Rokurokubi | Obake | Neck-stretching woman by night | Medium (surprise attack) | Moderate: Pin the neck or dawn’s light |

Symbolism

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Element | Earth—tied to grounded battlefields and enduring soil-bound relics |

| Animal | Horse—evoking the steed’s loyalty and the stirrup’s equestrian bond |

| Cardinal Direction | East—aligned with dawn patrols and imperial campaigns toward rising sun |

| Color | Iron gray—mirroring the stirrup’s cold metal amid fur’s muted earth tones |

| Plant | None prominent; occasionally sedge grass, as habitat overgrowth |

| Season | Autumn—harvest moons illuminate vigils over fading war blooms |

| Symbolic Item | Stirrup (abumi)—core form, representing interrupted journeys |

In Japanese culture, the Abumi-guchi is a powerful symbol of loyalty and loss. It represents the unspoken toll of the warrior code, bushido, highlighting how tools and weapons can outlast their intended purpose just as soldiers do, remaining silent witnesses to the effects of war.

This symbol reflects deep-seated fears of abandonment during times of conflict, tracing back to historical events (the Genpei War or the Sengoku period).

The unrecovered stirrup serves as a metaphor for widows waiting for their loved ones to return, as well as for artisans whose crafts fall into neglect during periods of peace.

Unlike restless spirits seeking revenge, this yōkai embodies quiet acceptance, encouraging people to find peace with the past. Proverbs like “The stirrup waits, though the horse is dust” remind us to approach both battles and life with patience.

This theme has carried into modern culture, inspiring episodes in manga series like GeGeGe no Kitarō.

During festivals like Obon, where lanterns are lit in memory of the deceased, effigies resembling the furry Abumi-guchi are placed on altars, blending Shinto ancestor worship with Buddhist ideas of detachment.

You may also enjoy:

Mara: The Buddhist Demon King of Desire and Death

October 13, 2025

Who Is Adrammelech in Demonology and the Bible?

October 1, 2025

Who Is Agares, the Demon of Earthquakes and Deception?

October 13, 2025

Si’la: The Seductive Jinn Who Lures Travelers to Their Doom

October 9, 2025

Who Is the Demon Andras, The Great Marquis of Discord?

January 15, 2026

Who Was Ravana in Hindu Mythology and Why Was He Feared?

October 3, 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Abumi-guchi?

Abumi-guchi is a tsukumogami yōkai from Japanese folklore, animated from a discarded samurai stirrup left on a battlefield after its owner’s death. After about 100 years of neglect, it transforms into a small, furry creature with the stirrup as its mouth and leather straps as limbs, embodying eternal loyalty rather than malice. This yōkai appears in Edo-period illustrations, symbolizing the quiet sorrow of war’s forgotten remnants.

How would the Abumi-guchi evolve if it were a real animal?

Suppose the Abumi-guchi were a biological entity rather than a supernatural one. In that case, it might evolve from small, burrowing mammals in ancient grasslands, adapting iron-mimicking mouth structures for foraging or defense amid human expansion. Ancestors could have resembled rodent-like scavengers that incorporated metallic debris into their diet for mineral enrichment, leading to a Linnaean classification under Mammalia, possibly in the order Rodentia, with unique osteo-dental adaptations.

What does Abumi-guchi look like?

The Abumi-guchi resembles a squat, woolly animal about the size of a rabbit, covered in shaggy brown or gray fur with a large, U-shaped iron stirrup forming its open mouth. Frayed leather straps from the original saddle serve as dangling arms or legs, allowing a shuffling movement, while its small, beady eyes convey a sense of perpetual waiting.

Where is Abumi-guchi found in folklore?

Abumi-guchi haunts abandoned battlefields and overgrown meadows in central Japan, such as sites from the Genpei War or Sekigahara, drawn to the spiritual residue of fallen samurai. These locations provide the neglect needed for its animation, with encounters often at twilight when wanderers hear phantom hoofbeats as omens. Unlike urban yōkai, its habitat underscores rural isolation, tying into Shinto beliefs about tools retaining warrior essences.

Is Abumi-guchi dangerous?

No, Abumi-guchi poses no physical threat; it is one of the most benign yōkai, lacking powers to harm or curse. Its presence might evoke emotional unease, stirring reflections on loss, but folklore portrays it as a passive sentinel awaiting a lost master.

What is the origin of Abumi-guchi?

Abumi-guchi originates as a tsukumogami, born when a samurai’s stirrup—abandoned amid the chaos of battle—gains sentience after a century of disuse, infused with the owner’s unfulfilled loyalty. Rooted in Heian-era animism, it reflects Japan’s feudal era reverence for tools as extensions of the soul, evolving in Edo folklore amid peacetime nostalgia for samurai valor.